Kirk Franklin

OCMS, UK

Abstract

Leadership and governance structures for any organisations involved in God’s mission need to come under review because of the growing influences of the interconnected globalised world. As Christianity moved farther away from the Christendom model of centralised control to other models of leadership and governance, other paradigms have been proposed along the way. One is called polycentric leadership and governance and is based upon principles of polycentrism. Using a case study approach assists in giving contexts for assisting the understanding of polycentrism in a world where Christian mission is adapting in a rapidly changing polycentric world. The case study explores leadership, governance and specific focus of one geographic region all within the context of the Wycliffe Global Alliance.

Keywords

Globalisation, polycentric leadership, governance, leadership structure, Christian mission, missional leadership

Introduction

Leadership and governance structures for organisations in God’s mission need to come under review because of many factors. One that is in focus in this paper is the growing influences of the inter-connected world known as globalisation. As Christianity moved farther away from the Christendom model of centralised control to other models of leadership and governance, other paradigms have been proposed along the way. One called polycentric leadership and governance based upon principles of polycentrism has emerged as a possible way forward for some contexts. Enthusiasm for this possibility continues to grow. However, at the same time, some degree of caution should be considered. Historian Stephen Neill warned 70 years ago that, ‘if everything is mission, then nothing is mission.’1 Likewise, if polycentrism solves everything, then nothing is polycentrism. Or, if everything is polycentric, then nothing is polycentric.

This case study assists in giving contexts for assisting the understanding of missional polycentrism in a world where Christian mission is adapting in a rapidly changing polycentric world. The case study itself is polycentrism at work within the ministry context of the Wycliffe Global Alliance in its leadership and governance, and then the specific focus of one geographic region of Latin America. The choice for making this a case study is because it is what Robert Yin calls a ‘real-world contextual environment.’2 Studying this particular case sheds ‘light on the wider phenomenon of which that case is an example.’3 The question is: How has polycentric theory and practice in mission been an outwork-ing of the development of the Wycliffe Global Alliance over the past decade?

Defining Polycentrism

For this study, polycentrism is defined as ‘the concept of allowing for self-regulating centres of influence within a singular structure. This occurs when there are many centres of power or importance within a political, cultural, or socio-economic system. The multiple centres may be of leadership, power, authority, ideology, or importance within a larger boundary or structure.’4

Since the context of this study is the Wycliffe Global Alliance (‘the Alliance’), it has defined polycentrism in the context of God’s mission as the use of ‘self-regulating centres of influence within the singular structure of the Alliance. This occurs as many centres of appropriate power, importance, influence, leadership, authority and ideology occur within the wider Alliance. Such centres of influence are to help the greater good of Bible translation movements.’5

My introduction to polycentric leadership in mission was not intentional. It was by accident in 2010 while researching an MA (Theology) in South Africa. At that time, two references stood out. First, researchers Philip Harris, Robert Moran and Sarah Moran in 2004 identified four ways corporations in the global arena were structured. They were either ‘Ethnocentric’ and operated with a monocultural philosophy; ‘Regiocentric’ that functioned as the collaboration of regional subsidiaries; ‘Geocentric’ with an interdependent worldwide system; and ‘Polycentric’ that rely on the local host-country managers to operate with ‘high or absolute sovereignty over the subsidiary’s operations.’6

Secondly, and due to the fact the research took place around the time of Edinburgh 2010, in the series preface of Regnum’s volumes, it was noted how the study process itself was ‘polycentric’ because it was ‘open-ended, and as inclusive as possible of the different genders, regions of the world, and theological and confessional perspectives in today’s church.’7 In the same volume authors, Daryl Balia and Kirsteen Kim described the past one hundred years as birthing a ‘polycentric world church’ re-shaped from the shift to the majority world.8 Balia and Kim also noted how the spread and growth of Bible translation take ‘place in a world where difference and diversity are increasingly recognised and encouraged, where the centre of gravity of the church is no longer in the “West”, where the predominance of one culture over others is no longer accepted, and where cultural polycentrism is a fact of our time.’9

These references about the influence of polycentrism upon the global church caught my attention but I did not explore it any further at that time. However, it contributed to some of the theoretical basis of PhD research in 2012. As that research came to a conclusion, observations and findings concerning polycentrism in the mission of God were published in these journals and books: ‘Polycentrism in the Missio Dei’ (HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 72(1) 2016); a chapter on polycentrism in ‘A Paradigm for Global Mission Leadership: The Journey of the Wycliffe Global Alliance’ (PhD thesis, University of Pretoria 2016); a chapter on polycentrism in Towards Global Missional Leadership (Regnum, 2017); and a section on polycentrism in ‘Leading in Global-Glocal Missional Contexts: Learning from the Journey of the Wycliffe Global Alliance’ (Transformation (1), 2019). These resources have helped make the findings available to other researchers. This paper builds upon that work.

Missiological Framework

Within the context of this case study, Charles Van Engen’s missiological framework of four domains of mission theology is loosely followed.10 The first discipline is the Bible as the source text for theologising in this study. This is interwoven with considerations from church and mission histories, followed by the contexts of the study that in this case are within the Wycliffe Global Alliance. Finally, are references to personal experience and in the author’s case both as a researcher, and a leader within the Wycliffe Global Alliance when the case was taking place.

Biblical Insights

Is the concept of polycentric missional leadership and governance biblical? There are indicators in the Bible of multiple voices (the Holy Spirit’s arrival upon those gathered at Pentecost), inter- cooperation (Nehemiah’s collaborative efforts in rebuilding the Jerusalem wall), and relationship and tension between centralisation and decentralisation (the Jerusalem church’s relationship at times with the regional churches the apostle Paul planted). Therefore, this brief overview is only intended to suggest some of the scope of polycentric thinking and behaviour in the biblical texts.

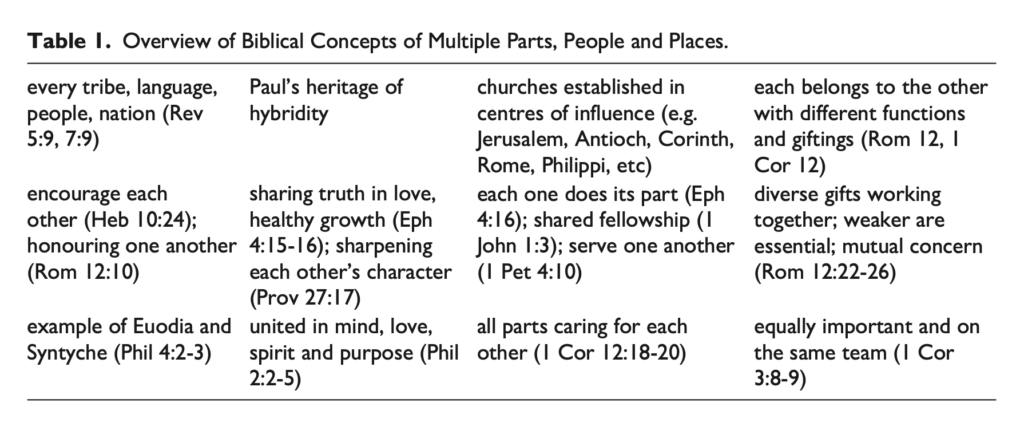

Starting in Genesis there is an example of what polycentrism is not. At a macro level, the desire to build the tower of babel showed what happens when humans behave as one with one culture and mindset: ‘The whole earth had a common language and a common vocabulary’ (Gen 11:1 NET). African theologians Barnabe Assohto and Samuel Ngewa observe how this was ‘an ideal situation if used properly [because] language is a gift from God. Words play a major role in our relationship with God and constitute a marvellous tool for building ties between people.’11 However, in this situation, the omniscient God was being supplanted by the singularity of thought and might that humans had when they had one voice, language, mindset and culture. The people collectively using their minds and abilities to focus on one task was not what God had in mind for their purpose of spreading out and taking care of his creation. His action took care of that: confusing ‘their language so they won’t be able to understand each other’ (Gen 11:6-7 NET). This was an example of a singular centre of influence. God’s action would result in multiple centres of influence. And we get the end picture of what that looks like in Revelation 5:9 (NET) ‘you have purchased for God per- sons from every tribe, language, people, and nation’ and 7:9 (NLT) ‘a vast crowd, too great to count, from every nation and tribe and people and language.’

Moving on to the apostle Paul (Saul), in his heritage is a uniqueness of hybridity: his father while being Jewish had highly prized Roman citizenship. Paul was born and raised in Tarsus, a Hellenistic (Greek) city in Asia Minor and therefore was diaspora. As NT Wright observes, the ‘Jewish world in which the young Saul grew up in was itself firmly earthed in the wider Greco- Roman culture.’12 After Paul is set apart with Barnabas (Acts 13), he and his missionary bands spent considerable time in a variety of urban centres in the region. These were also Jewish diaspora centres that provided Paul and his missionary band with synagogues where they could meet with people, but also ‘marketplaces, lecture halls, workshops and private houses.’13 The trade routes that intersected at the urban centres meant that Paul’s teaching spread to people in surrounding areas.

Viewing this through polycentric thinking, the gospel spread through multiple centres of influ- ence involving people and places from some diversity of culture and perspectives. Some of the places Paul and his bands visited were: (1) Antioch of Syria (Acts 13:1; 14:26), the third-largest city in the Roman Empire and an important centre of early Christianity. The church there sent out Paul and Barnabas and Paul reported back to it; (2) Jerusalem (Acts 21:17), the Holy City as the place of the birth of the Christian movement with the location of the ‘mother’ church; (3) Athens (Acts 17:16), the most important cultural centre (arts, learning and philosophy) of that time. Its cultural and political achievements impacted the rest of the region; (4) Corinth (Acts 18:1), the commercial centre for trade between west and east, a place known for its great temple dedicated to the goddess Aphrodite; (5) Philippi (Acts 16:12) a regional city where the first believers included businesswoman Lydia from another region Thyatira and a person of ‘some wealth [and] means’14;(6) Ephesus (Acts 18:18; 19:1), a city known for its affluence, with a large harbour, an important commercial centre and its famed Temple of Artemis; and (7) Rome (Acts 28:14), the capital of the expansive Roman Empire and influential on many fronts including politics, economics, art and science.

This scan of localities shows how the emerging church was located in multiple geographic contexts with a diversity of religious, cultural and sociological influences. How appropriate then for Paul to write to the Roman church about the inner workings of the body of Christ being like the human body with its multiple and different parts. Each is supposed to work together with their different functions and giftings and importantly, ‘each member belongs to all the others’ and helps the body with a diversity of gifts service (Rom 12: 4-5 NLT) ‘for the benefit of all’ (1 Cor 12:7 NET) ‘[a]s each one does its part, the body builds itself up in love’ (Eph 4:16 NET) because it is a body whose ‘members who belong to one another’ (Rom 12:5 NET).

Members of the body ‘encourage each other. . . on to love and good works’ (Heb 10:24 NET) and devotion to each other ‘with mutual love, showing eagerness in honoring one another’ (Romans 12:10 NET). Christ connects the various parts of the body and each part has a unique personality and gifting. Community takes place within this body for fellowship— a reality shared in common (I John 1:3 NET). Each member of the body has a gift to use, and it is ‘to serve one another as good stewards of the varied grace of God’ (I Pet 4:10 NET). The gifts given are diverse but intended to work together for the common good. The ‘weaker are essential’ (v22) and there is no division in this body and instead of ‘mutual concern for one another’ (v26) to the extent that each part share in each other’s joy and pain. Ministry within and by the body builds upon the efforts of the different parts and regardless of the role, each is ‘equally important and on the same team [as] coworkers with God’ (1 Cor 3:8-9a TPT). The members of the body are not in competition with each other or vying to be more important than each other. Indeed, Paul states: ‘God has put each part just where he wants it. . .. This makes for harmony among the members so that all the members care for each other’ (1 Cor 12:18-20, 25 NLT).

Paul also emphasised the need for Christians in all of their differences to be transparent with each other and to apply ‘the truth in love,’ so that the body grows and becomes healthier and fruitful (Eph 4:15-16 NLT). Helping each other grow means one’s character is developed when there is constructive criticism between friends, colleagues or co-workers. ‘[a]s iron sharpens iron, so a person sharpens his friend’ (Proverbs 27:17 NET). This differing results in something better.

There is to be unity within the body even though the composition is diverse. Christ it together and spurs each part of the body to ‘be of the same mind, by having the same love, being united in spirit, and having one purpose’ and to treat each other as more important than oneself (Phil 2:2-5 NET). Paul singles out those who co-labour with him: ‘I appeal to Euodia and to Syntyche to agree in the Lord. . .. They have struggled together in the gospel ministry along with me and Clement and my other coworkers, whose names are in the book of life’ (Phil 4:2-3 NET). The two women mentioned had served well in the past but now needed help in resolving a difference between them. Paul’s naming of people in this passage shows how he knew these co-workers by name.

In summary, we see what happens when there is only one type of character, opinion or determination, such as the desire to build a tower and therefore supplant God. In contrast, there are many references to multiple parts, centres, leadership, people, involved in ministry and working together to build God’s kingdom. This is illustrated in Table 1:

Through the apostle Paul’s movements, a wide range of new centres of influence are established with the early church. There is the interconnection of a diversity of parts, such as people and their talents, opinions, character, culture, worldview and so forth, but all being unified to display Christ’s love and to achieve his purpose as a diverse body but working towards a unified whole. There is an example of constructive criticism from one or more voices towards another with the intention of a better outcome or improvement. There are examples of some of the actual people whose names are shared and have their problems and challenges and may not be agreeing with each other or working together as they should, but are still acknowledged and given the vision of what can happen when those differences can be sorted out. These are examples of similarities with polycentric thinking and behaviour.

The Polycentric Church

How far back does one need to go to find missiologists and theologians describing the church as multi-centred? An early reference was Tite Tinéou’s description in 1993 of the ‘polycentric nature of Christianity’ about the ‘formation of indigenous theologies.’15 Charles Van Engen made these observations in 2006: ‘[i]n reaction to the hegemony of the Western church in theology, many theologians from Africa, Asia and Latin America affirmed a polycentric perspective of theologising’;16 ‘pluriformity and polycentricity of the one church necessitate our learning to be a glocal church involving the simultaneous, constant, dynamic interaction between the glocal and global.’17 Van Engen also observed how ‘mission sending is now polycentric: Cross-cultural missions send their missionaries from everywhere to everywhere.’18

In 2006, Tiénou described how both identity and theology was influenced by the ‘[p]olycentric. . . Christian faith with many cultural homes [and] at home in a multiplicity of cultures without being permanently wedded to any one of them.’19 Kirsteen Kim elaborated in 2009 about the historical reality that there was not one centre of the Christian faith of the past 500 years:

when European Christianity was at its height, there were many Christians whose allegiance was to Orthodox patriarchs in Asia and Africa. And within Europe Christianity was polycentric, with Catholics looking to Rome, Protestants to the German heartlands of the Reformation, and Orthodox Christians looking to Athens, Moscow, or another capital depending on which autocephalous church they belonged.20

Moving from a macro view to a micro level within the context of leading in local churches, JR Woodward in 2012 pointed out the ‘vulnerabilities of central leadership structure[s]’ and offered the solution of a ‘shift from a hierarchical to polycentric approach to leadership.’21 His thinking was influenced by Suzzane Morse’s sociological study on behavior in communities with

circles of leadership to create a system for the community that is neither centralized nor decentralized, but rather polycentric. The polycentric view of community leadership assumes there are many centres of leadership that interrelate. . .. The polycentric model looks at the vision and finds avenues for the community’s many constituencies to work together on the most appropriate ways to contribute to that goal. No longer does responsibility rest with one group or board. The tasks of deciding and acting are assumed by a wide range of people.22

In the context of Bible translation, the polycentrism of cultures and languages has been a reason that the Bible’s translatability has been a vehicle for the spread of Christianity across the globe, demonstrating that it is ‘at home in all languages and cultures, and among all races and conditions of people.’23 The Bible’s translatability bears witness to its adaptation into the local context of any language and culture.

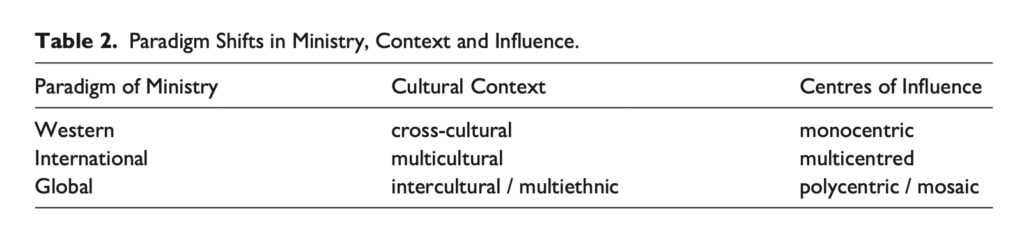

In the Western ministry paradigm, mission was from western nations to the rest of the world and therefore cross-cultural in orientation because people going from the West to other places had to function in some form of cross-cultural engagement. As mission became international where churches and agencies had their offices spread in other countries (such as in Europe, Asia and Latin America), multi-cultural became a depiction of what was happening because many cultures were having to relate to each other. Now, with the global church and corresponding global mission movements, this is intercultural space. Another possible term is multiethnic. Phil Smith in his recent doctoral studies defines this in the context of Christian ministry as ‘the variety of backgrounds found in God’s growing family, including racial, cultural, national and linguistic differences.’24 These paradigm shifts can be diagrammed in Table 2.

In summary, some theologians have connected the church’s theologising, spread, structure and missionary response as polycentric, meaning multiple centred, rather than emanating from one centre. Historically, this is not a new concept since the Christian faith has had multiple or polycentric places of influence and what Kirsteen Kim also referred to as a ‘mosaic of churches and communities.’25

Wycliffe Global Alliance

Polycentrism can be associated with the multidimensional social process and interconnection that multiplies and intensifies social interactions in globalisation. Through globalisation, the concept of multiple, or polycentric centres of influence becomes more viable. The interconnectedness also increases the likelihood of information exchanges between practitioners and theorists of polycentric leadership. This is the theoretical framework for this case study of polycentric leadership and governance within the mission agency called the Wycliffe Global Alliance. The case is a means to share what has been discovered with the aim that this may assist others who are interested in exploring polycentric thinking and practice, especially in the context of God’s mission.

Historical Development

In 1942, Wycliffe Bible Translators (WBT) was formed by William Cameron Townsend and William Nyman at Nyman’s house in California. The purpose was to recruit Christians and raise funding and prayer support for Townsend’s other organisation, at the time called the Summer Institute of Linguistics (now SIL International), that was working in Mexico in linguistic analysis, literacy and Bible translation with and for minority language groups. Since the work was quickly growing, Townsend needed a US-based missionary sending organisation for his field-based Christian scientific research organisation.

Over the next 40 years Wycliffe grew with new sending bases in many Western and Asian nations. These ‘divisions’ as they were called at the time because they were subsidiaries of the first Wycliffe organisation in the United States, were sending their resources to SIL. By 1980, the group of divisions were called Wycliffe International (WBTI) and represented a growing worldwide pres- ence. In 1999, Wycliffe and SIL adopted Vision 2025—a desire to see Bible translation started in all the remaining languages that needed it by the year 2025. This called for new ways of working including intentionally engaging with the global church. In 2003, the Wycliffe International board made this declaration:

Based on our growing excitement about what God is doing in the worldwide church, our sense of where we are in church history, and its significance in achieving [Worldwide Engagement of the Church], MOVED to foster an environment in which member organizations are encouraged and assisted to engage in appropriate partnerships with churches of the South and East.26

Up until this time, WBTI and SIL had the same Executive Director, leadership team and overlapping board. The International Administration was based in a large headquarters in Dallas, Texas. As WBTI sought to position itself for ministry in the 21st century, it decided to start a process of separating the leadership team from SIL, of having completely separate boards, and of having its own Executive Director, separate from SIL. These changes were started in 2006 and in 2008 were completed when WBTI’s first Executive Director took the lead and moved the operational headquarters from Dallas to Singapore but more importantly, set up a culturally-diverse leadership team that worked virtually, spread across the globe, rather than in a centralised office. The reason was to develop a structure for WBTI to better engage with the church worldwide.

The way the new leadership team sought to work together was to ensure that all of the 12 cultures represented on the 15-member team learned to respect each other with good interpersonal relationships and open communication, celebration and trust. The team sought to be flexible, cope with change and be responsive to the opportunities God would give them. They sought to have alignment with each other and be a reflective learning community that was always learning from each other from within the movement. The team sought to develop habits of prayer and sensitivity to the Holy Spirit. The team was visionary, creative, servant leaders who were stewards over all that God had put in their hands.

In 2009, a process was well underway that sought to bring together two unique classifications of organisations within WBTI: (1) The Wycliffe Member Organizations were the original Divisions as well as some newer Wycliffe sending organisations, along with the original National Bible Translation Organizations. These three groups had done reasonably well to interrelate with each other. This group was not growing in size. (2) There were also Partner Organizations. These did not have any of the ‘Wycliffe DNA’ but wanted to be recognised by WBTI because of their commitment to being part of the Bible translation movement. This group was growing in size, and the majority came from the majority world. By 2010 there were 46 Wycliffe Member Organizations and 60 Partner Organizations of various shapes and sizes.

Over the next six years, various efforts were made in changing the governing legislation of WBTI to bring the two groups into one. This necessitated doing away with seven organisational categories and sub-categories. In 2011, WBTI adopted the doing business as name of ‘Wycliffe Global Alliance’ to align itself with what it was structurally becoming—an alliance of interrelated organisations who chose to work together within the global Bible translation movement. It defined an alliance as ‘a collective of interdependent organisations that are bound together through a formal agreement made to advance common goals and secure common interests.’27 Specific to the Wycliffe Global Alliance that serves with and is a part of the global Church, is how the Alliance is a community of organisations with the common goal to ‘nurture an environment in which like-minded organisations can fully participate and serve together in God’s mission through Bible translation movements and related ministries.’28

What was significant about purposefully identifying as an alliance, was to differentiate what it had been, an institution with the ‘inheritances of valued purposes with attendant rules and moral obligations. . .. The institution focuses on preserving and providing structures for the safeguarding of core purposes.’29

In 2015, the 29 Wycliffe Member Organizations that held voting rights over the affairs of the Wycliffe Global Alliance agreed to give up their exclusive responsibilities and extend this right to all organisations that met the criteria of belonging in the Alliance. These criteria included seven streams of participation that covered all manner of ways organisations were recognised in contributing to Bible translation. It also included entering into a Covenant/Statement of Commitment between the individual organisation and the Alliance. It also included an agree- ment to contribute financially to the operating budget of the Alliance. These agreements were completed and signed by the respective leaders by early 2016. Over 100 organisations entered into this new arrangement. Each organisation identified what its best contributions were to the Bible translation movement. Included in this group was a growing list of church denominations from the majority world that were setting up Bible translation functions and wanted to do this in fellowship with the Alliance.

In summary, since its inception from Wycliffe Bible Translators, to Wycliffe International and then the Wycliffe Global Alliance, demonstrated that it could adapt and adjust to changing contexts so that its core purpose and ministry had an ongoing positive impact. As the church became global, Wycliffe International intentionally adapted to create ways for the church to participate in the Bible translation movement. Through the whole journey, this required what David Bosch called ‘bold humility’ and an interdependent will and spirit.30

Polycentric Influences in Wycliffe Global Alliance

The political associations of polycentrism have implications for the Wycliffe Global Alliance’s governance and structure because as a global alliance, the 100+ self-governing organisations collaborate as a community but retain their distinctions. There are four noticeable ways that polycentrism occurred, expressed through these transitions:

- The ‘West to the rest’: The Alliance moved from being an organisation that only sent resources from the West/North to the rest of the world, to a global movement for Bible translation. Rather than remaining centred in North America, where Wycliffe’s roots were, its global expression relocated to Singapore in 2011 (and now operates virtually) with a leadership team a governing board that is intercultural representing more than a dozen countries between the two bodies. And of the 100 organisations that comprise the Alliance, 70% are from the majority world. There are multiple centres of influence and polycentric places of spiritual vitality and mission influence impacting the Alliance in a positive and dynamic sense. They come from Kenya to South Korea, from Papua New Guinea to Paraguay, from Singapore to South Africa.

- A Western mission agency to an international organisation to a global alliance of mission agencies and churches. This shift was structural because when Wycliffe Bible Translators was formed it created operating units in other countries, similar to the concept of post-World War II military divisions, all centrally controlled from the United States. Now, it is an alliance of like-minded organisations, with movements collaborating together for Bible translation around the globe. The alliance structure is a polycentric concept of many centres of leadership interrelating—from the individual, interdependent and diverse Alliance Organizations, to the Alliance’s Area Directors; from those to the rest of the Alliance’s leadership team; then to the Alliance’s board and back again to the Alliance Organizations’ boards, and so forth in an informed spiral. This interconnected leadership web identifies the vision for the community and then finds opportunities for its many organisations to make decisions, collaborate and act together in suitable ways to reach the goal.

- An assortment of self-governing autonomous organisations to an alliance of self-governing organisations behaving and working together as a community of friends in God’s mission. The organisations that make up the Alliance operate as a polycentric interconnected leadership. The Alliance’s leadership team guides the Alliance and ensures it is committed to its vision and enables all of the Alliance Organizations to collaborate in a community. The individual leaders of the Alliance Organizations can participate in the collaborative workings of the wider Alliance. As a result, the polycentric leadership operating within the Alliance creates a learning environment where its leaders collectively reflect together and act collaboratively. The glue that binds the Alliance is its ideology, which is also the fuel that enables it to move forward. Since the various circles of polycentric leadership associ- ated with Alliance are culturally diverse, there is a growing attitude of openness and curios- ity, an awareness of otherness, and a readiness to learn from each other. This model operates with people of equal authority who pursue wholeness in the community.

- A centralised international institutional structure to a decentralised hybrid alliance structure. The newer form of the structure resembles many aspects of a decentralised structure. Yet, in reality it maintains some vestiges of institutionalism, because of operational requirements such as maintaining its financial systems and standards, governance requirements, and how it maintains accountability from its organisations. The Alliance’s current structure is therefore not centralised or decentralised, but it is polycentric, depicting a hybrid model, with a bottom-up approach with some degree of control, structure and centralisation amid decentralisation.

Within the Wycliffe Global Alliance, an emerging polycentric paradigm for global mission leadership has occurred because there is a movement to mitigate autocratic effects of established centres of power in the areas of structure and centralisation. There has been decentralisation through a means of a bottom-up approach with some degree of control. The results are: (1) leadership in the Alliance is from among and with others; (2) leadership is influence from creatively learning together in community and to attentiveness to the others in the community; and (3) leadership of the Bible translation movement has shifted from one organisation to many and the global church is represented and engaged in what was a Western institutional structure and practice.

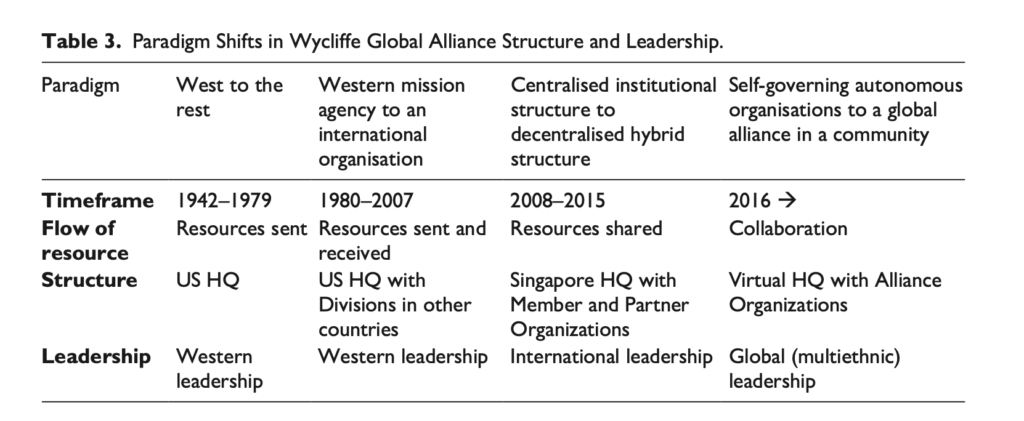

Reflected in Wycliffe Global Alliance’s structure are the these influences of polycentrism: (1) the ownership and responsibility for mission has shifted from Western countries to polycentric places of influence and spiritual vitality across the globe Balances global spheres of influence, manages dependency from Western resources through influence from the majority world which create new opportunities, practices, equalising authority and revolving leadership and incorporates new places of influence and spiritual vitality, all of which is mirrored in the Alliance’s composition; (2) the Alliance operates in an interconnected leadership web with many centres of leadership interrelating together; (3) the circles of polycentric leadership within the Alliance are culturally diverse, creating mutual learning with an awareness of others; and (4) the Alliance’s leadership and governance structure is polycentric with decentralisation accompanied by limited control over the 100+ self-governing organisations that make up the alliance that collaborate together as a community and retain their individual distinctions. The shifts in the Wycliffe Global Alliance can be summarised in Table 3:

In summary, through a polycentric structure, the Wycliffe Global Alliance has shifted its focus from operating as an institution to being on a journey as an alliance within the Bible translation movement. To this end, the Alliance has been developing polycentric leadership across the globe so voices from all of its organisations are involved in the vision.

Key Terms as Outcomes of Polycentrism

In the change process, aligning Wycliffe Global Alliance thinking, actions, and processes has taken place to reflect its global nature and its desire to be positioned in God’s mission, not in pursuit of its mission. In this process, conversations throughout the Alliance around topics and issues resulted in a set of terms and definitions that became foundational in expressing the Alliance’s intent. These discussions were polycentric because they involved multiple voices and locations over many years of interaction. As a noticeable result, each of these terms and definitions provides foundations from which polycentrism takes place and influences how the Alliance continues to define its fundamental purpose and future31:

- Collaboration—Takes place when the leaders and/or staff of two or more Alliance Organisations decide to deliberately think and work together to achieve something in God’s mission. It is an outcome of the intentionality of strengthening friendship in God’s mission, which leads to greater partnership and generosity because the value of each of the partners is recognised and affirmed. It is only when collaboration and partnership are grounded in true community that we can see and experience what God intends.

- Friendship and Community—Friendship with God, with each other, and with those whom we are called to serve is a fundamental missiological principle for the Alliance because it gives God glory and serves as a visible demonstration of God’s kingdom. Friendship takes place within and also creates and deepens community.

- Stewardship and Generosity—The Alliance gives intentional space for the strengthening of friendship leading to greater collaboration, partnership and generosity, as the value of each Alliance Organizations is recognised and affirmed. Generosity becomes a natural response as the Alliance lives and serves in community. Good stewardship becomes the habitual behaviour of friends serving together within God’s mission. Stewardship and generosity encompass all of life and include time, service, compassion, grace and our whole being, not only our finances. Stewardship and generosity envision all of God’s Church as both givers and receivers.

- Third Spaces—Deliberately creating safe spaces that enable different groups within the Alliance to come together to acknowledge, explore, discuss, understand, celebrate, reconcile and create new friendships, ideas and concepts in and for God’s mission. Each part of the body is needed, and our role has been to ensure that the body is healthy, growing and effective. Rather than approaching a conflict or decision in a binary sense: a ‘right’ way or a ‘wrong’ way, a preferred method is to negotiate a third way. This creates interdependent cooperation of giving and receiving and serving together across the global Bible translation movement. In this way, all parties demonstrate respect and dignity in authentic partnerships that are based on genuine friendships in mission.

Through these definitions, the Wycliffe Global Alliance created a vision of a generous friendship in a community as it stewarded its responsibilities that included unique ways of strengthening relationships. In this journey of deliberately engaging polycentrically within the Alliance, another development was to consider polyphony and its application within a missional community like the Alliance. So, it defined a ‘polyphonic community’ as ‘many voices listening to and harmonising with each other as friends in God’s mission. God leads through his Spirit, and he speaks through any number of people regardless of their role, status or culture.’ The result is a vibrant community of Christ-followers that ‘experiences the beauty of diversity and how each part blends within the symphony of chords of voices.’32

Polycentric missional leadership has the opportunity and responsibility to develop collaborative environments that generate generous spaces and places for learning, listening and voicing.

The Significance of Polyphonism

Christina Walker in her research on inclusive multicultural teams noted how in such contexts, leaders may give attention to creating environments of ‘attentive space. . . where the leader and team members are paying attention to each other through an ongoing invitation to learn, listen, and voice.’33 This space is ‘full of learning, listening, and voicing’ in an atmosphere that is ‘physically and physiologically open for diverse contributions with freedom for the members to be, reflect, and grow.’ 34 It is sustained and supported through creating a secondary ‘temporal space’ which is ‘a pace that creates attentive space’35 and ‘proximate space’ where there ‘is a gathering of people together in physical nearness on a regular basis in order to create attentive space.’36 Walker’s approach is designed to help global leaders navigate challenges of adapting to constant change, managing the ‘creative abrasion’ that is not destructive from diverse perspectives, and managing the inherent tensions of both ‘belonging and uniqueness.’37

As an example of creating deliberate listening processes within the intercultural Wycliffe Global Alliance, it held five missiological consultations involving a total of 145 participants from 51 nations. In addition to discussing the topic at hand (funding God’s mission), the intentional environment created enabled participants to develop relationships, listen to diverse voices, gain insights and discern together opportunities and responsibilities regarding the topic. As a result, participants learned of the importance of concentrating on building ‘real relationships,’ which in the context of mission partnerships, provides the opportunity to ‘learn from partners and what they can bring to the table’ and in doing so, learn to listen because ‘two-way accountability in our relationships; our relationships with God and with each other are most important.’38

‘Let every person be quick to listen. . .’ (James 1:19b NET) is a reason why the Wycliffe Global Alliance purposely makes space for multiple voices to be heard. When these voices blend in community, they produce a harmonious chorus. The Alliance calls this ‘polyphony’ as it gives a language and entry points for deeper discovery of God’s mysteries because instead of listening to a single note, participants hear a symphony—the performance of a harmonious chorus that is both beautiful and stirs towards the heart of God and his mission. This is the beauty of the diversity of God’s global church involved in his mission. In this chorus include the voices of children, men and women, Irish, Cameroonian, Australian, Swiss, Burkinabe, Mexican and so forth, each with a slant of his or her worldview.

While this can start to sound like heavenly music what is melodious music to one may be jolting to another and vice versa. The apostle Paul emphases the clarity of hearing as a challenge for leadership: ‘Even lifeless instruments like the flute or the harp must play the notes clearly’ (1 Cor 14:7 NLT); or ‘unless they make a distinction in the notes, how can what is played. . . be understood?’ (1 Cor 14:7 NET). They have to make ‘meaningful sounds if people are to respond to a tune.’39 Applied to the history of the modern missionary era, it was set to a Western tonal system. But that is not what the polycentric global church sounds like today.

Wise speech is important especially when it comes to people who are careful with their words. The writer of Proverbs 10 states ‘the teaching of the righteous feeds [or shepherds] many’ (v21 NET); or ‘[t]he speech of a good person is worth waiting for’ (v21 MSG). Proverbs 15 emphasises the importance of listening and using words wisely. For example: ‘The tongue of the wise treats knowledge correctly’ (v2 NET); ‘[s]peech that heals is like a life-giving tree’ (v4 NET); ‘[t]he lips of the wise spread knowledge’ (v7 NET); ‘with abundant advisers [plans] are established’ (v22 NET); and ‘whoever hears reproof acquires understanding’ (v32 NET). Listening to the words of wise counsel may include being an abundance of people and their voices.

Polyphonic hearing from widening circles of people may not lead to something better. It can be the opposite, to the clamour of cacophony. This can happen in politics and other social movements. Louder voices may not be the desired ones. Within the church environment, there can be leaders rising and say they are ‘speaking’ for God while others say God’s ‘voice’ is ‘hate’ speech.

During a symphony, the conductor’s role is important. If some of the violinists start going out of sync with the rest by playing too fast, a good conductor will turn to them with her left index finger pointed to the end of her baton, signaling the problem. The violinists immediately get back into harmonisation with the rest of the musician and thereby honour the conductor’s interpretation of the musical score. In the Wycliffe Global Alliance, the conductor’s baton is all of the foundational statements of values, ethos and direction of the organisation. The governing board and leadership team act as the conductor that interprets the composition. The musicians represent all of the organisations that make up the Alliance. This also means that the Alliance leadership has a responsibility for the softest, weakest musical instrument or voice to be heard, and not only heard, but be taken seriously. Situations have to be managed of cacophony caused by individuals claiming false power and the importance of their message. People should be able to speak, and their message heard. The conductor, operating from a position of love, love for making music in symphony and honouring the intent of the composer, uses the baton to give guidance that brings cacophony into polyphony. The individuals in the symphony honour the conductor’s interpretation of the music.

The traditional African chieftain’s governance role is carried out through listening to the senior advisors when a decision is to be make. The advisors interact and listen to the community and discern, interpret and make recommendations to the chief. If the chief is wise, he will listen and discern well. The voices that want to be heard must know that they are heard, and the governance structures need to interpret what they have heard, and with all the information at their disposal discern the way forward and will be respected for the direction they are giving. The Wycliffe Global Alliance has used regular missiological consultations that give polycentric and polyphonic space for participants to meet and express themselves. The chief, representing the Alliance leadership listens to the discussions and with a counsel of wise people crafts statements from the consultation that provide direction for the future.

In the polyrythmic aspect of African dance, different rhythms are layered over one another and adding the idea of polycentrism, movement can begin from any part of the body. Parts of the body dance to different instruments that are playing at different rhythms. Likewise, in a governing process, the Alliance board gives equal space to each member of this body. The governing board guides the whole body in the right direction while helping all participants differentiate between polyphony and cacophony. There is space for cacophony, but then someone or a process directs the cacophony into a symphony because when a governing board speaks, it does so with one voice. Is this managed in a contractual way when someone is playing out of tune or, is it managed through pointing the musician to the Alliance’s values and ethos that bring the Alliance community together?

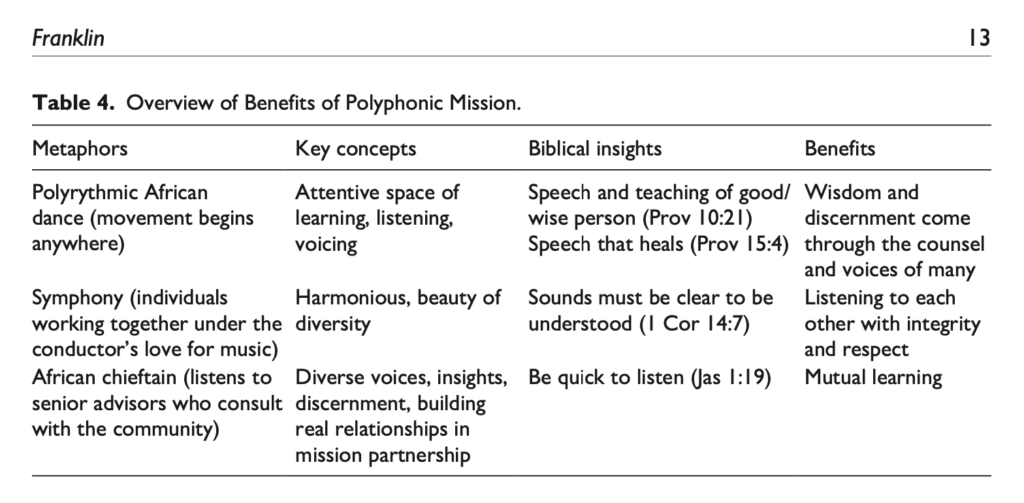

Before starting to sound idealistic or utopian, consider some potential areas of difficulty with being polyphonic: Can a ministry be truly polycentric without being polyphonic, otherwise dominate voices, whether individuals or organisations or both, take over. To be effectively polyphonic there must be better ways to listen and discern well together in community. It is difficult to listen when there is no quietness and discerning with the Holy Spirit and his community of people. As we listen, we treat each other with integrity and respect. As we seek to be a community of God’s people serving in his mission, then all of these observations become values of being in and part of an active community that learns to listen and discern together. Through giving processes and room for multiple voices to speak, and to learn to listen together in community can energise mission movements. Insights about polyphony can be seen in Table 4:

Polyphony (that contributes to constructive understanding and dialogue) and polycentrism (that incorporates and builds on the local knowledge, initiative and aspirations of the various centres of influence) in God’s mission requires learning, wisdom and sensitivity guided by the Holy Spirit. It is within the composition of worldwide church with its diversity and beauty of size, ethnicity, men and women, younger and older that participants are blessed beyond what they may realise because of God’s polyphonic-polycentric global body.

Exploring a Polycentric Governance Model

It is one thing to consider what a polycentric-polyphonic organisational dynamic might look like and be led. However, governing it is another matter. Take the Wycliffe Global Alliance board of directors for example. It is an eleven-person board that is elected by the 100 Alliance Organizations. The board members represent the Alliance’s five geographical regions of the world. There are a mix of men and women, some with pastoral-theological backgrounds and others with business and not for profit experience. Reporting to the board is the Executive Director who manages the leadership team, whose purpose is to act as a discerning community of global missional leaders that influences and inspires Bible translation movements, while encouraging Alliance Organizations to fulfil, in community, their participation in God’s mission.

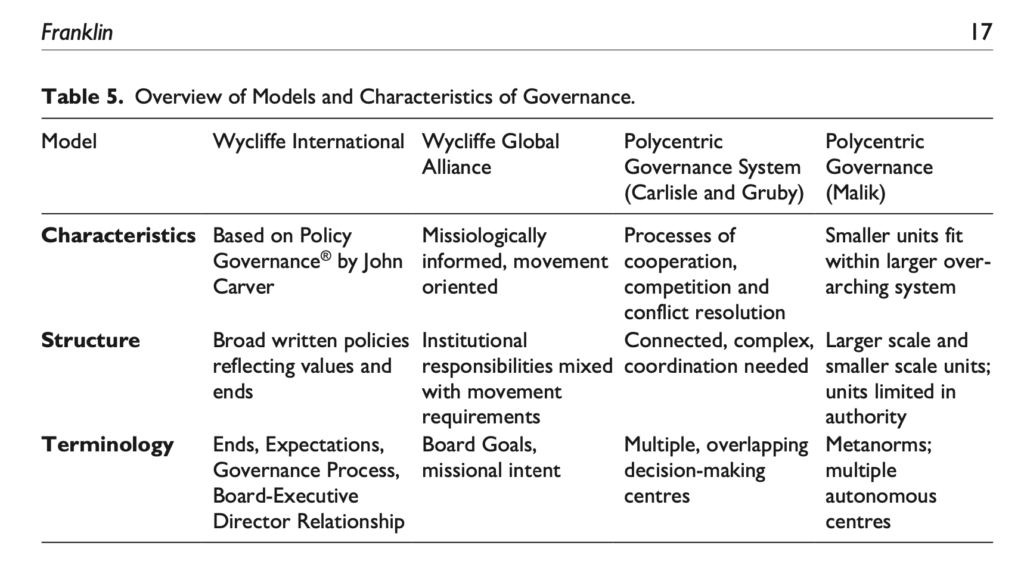

It is generally agreed in good governance that boards exist to give oversight, input and direction. Boards have a level of responsibility for the reputation, health, wellbeing, integrity and legal and financial soundness of an organisation. Going back to the late 1990s, the Wycliffe International board loosely followed Policy Governance® by John Carver. This meant the board directed, controlled, and inspired the organisation through broad written policies reflecting the organisation’s values and perspectives about goals to be achieved and means to be avoided. The written policies covered four broad categories that were consistent with Policy Governance® but used slightly different terminology: Board Goals, Expectations, Governance Process and Board-Executive Director Relationship.

As Wycliffe International became Wycliffe Global Alliance it found weaknesses in its governance model because of the high level of precision required was difficult for an intercultural board to meet and the governance model did not fit what the Alliance had become and therefore the board struggled to reconcile the two. Strictly following the methodology leads to board members losing interest in detailed understanding and monitoring of the organisation’s activities. At times the board found it hard to follow its policies which it had inherited from previous eras. Governing the Alliance of 100 other organisations, each of whom had their boards, was a challenge because the Alliance had become a movement supporting and encouraging movements, but still held some institutional responsibilities such as legal and financial accountability. Traditional board structures were designed to preserve and protect institutional responsibilities. The responsibilities of a movement are to adapt and change. These are two very different sets of needs. New board members found a steep learning curve to understand the Alliance and how it and its needs may differ from other organisations. The Alliance needed voices into its governance process that might not be typical ‘board material’ or who might not see themselves as wanting to be on a board. Since it was a missional movement, it needed to discern at a board level what is theologically and missiologically sound, not just following traditional corporate models.

This set the context for a discussion about a new governance model that would better serve the Alliance. Keith Carlisle and Rebecca Gruby express this well in that polycentricity is ‘a complex form of governance with multiple centers of semiautonomous decision making.’40 The Wycliffe Global Alliance looked into this during its April 2019 board meeting where two models of polycentric governance were considered: 1) Carlisle and Gruby; and 2) Malik. These are now explored in the context of relevance to the Alliance.

Polycentric Governance Systems (Carlisle and Gruby)

This system has two features: (1) ‘multiple, overlapping decision-making centers with some degree of autonomy’; and (2) ‘choosing to act in ways that take account of others through processes of cooperation, competition, conflict, and conflict resolution.’41

Applying these features to the Alliance context means that the decision-making centres are the leadership team and staff and churches and mission agencies (referred to internally as Alliance Organizations) interrelate with each other ‘in processes of cooperation, competition, conflict, and conflict resolution.’42 This system is not intended to function as a ‘tidy and static network of dis- crete, connected decision-making centers. Rather, it is a dense and evolving web of decision-making centers—some transitory and others relatively fixed.’43 The overlapping and multi-level nature of the decision-making units is ‘nested at multiple jurisdictional levels (e.g., local, state, and national).’44 The overlap ensures redundancy, so in the Alliance if any single organisation—church or agency fails, the ministry can continue. The system works if it is coordinated rather than an assembly of widely distributed but autonomous Alliance Organizations. This requires information exchange between decision-making centres so they benefit from knowing what policies instituted by others may have succeeded or failed. Without this interchange, the governance system’s ability to adapt at the pace of change would fail.

Maintaining accountability in polycentric governance systems may be difficult because of the multiple decision-makers, each operating within their accountability structures. Independent third parties may be required to monitor accountability.

Alliance Organizations can exert different levels of financial and political power over each other to further their interests. Such ‘power asymmetries. . . may inhibit the intended functioning of a cross-scale linkage.’45

Processes to manage conflict resolution within polycentric governance systems are important to its orderly functioning. These mechanisms may be informal or formal allowing for the diversity of governance already at play within the Alliance structure through the individual boards of the organisations.

In summary, polycentric governance systems do not necessarily operate better than other forms of governance because of its complexity, coordination that is required, challenge to hold decision-makers accountable for performance, and dispersion especially in larger or geographically systems like the Wycliffe Global Alliance. However, polycentric governance systems have the advantage of ‘better access to local knowledge, closer matching of policy to context, reduction of the risk [of failure] on account of multiple avenues for policy experimentation [and] improved information transmission due to overlap’46 among the various decision-making centres.

Polycentric Governance (Malik)

Anas Malik summarises a ‘polycentric system [as] one where individuals [can] organize and devise rules for multiple government authorities at different scales’ so that smaller units such as local governments fit inside the larger system and benefit from the ‘overarching order’ of that system and no one unit is ‘allowed to exercise unlimited authority.’ 47 This is in contrast to monocentric governance operates under a central authority [that] monopolizes collective choice [and acts] as a unitary sovereign rule-giver.48 Whereas the system of federalism ‘is a type of polycentric order’ and operates with ‘two levels of government rule over the same land and people’ both levels have some degree of areas of autonomy.’49

Malik’s model features ‘metanorms’ that are formalised over-riding norms that support self-understanding among individual units that considers the interests and perspectives of other units in creating ‘associations and relating to other associations.’50 These metanorms are pervasive and durable and act as powerful, though often unwritten, guides to what is acceptable and appropriate within the structure. Metanorms provide a basis of ‘shared understandings that allow diverse collective choice units to coexist, with mutual understandings of domains of autonomy.’51 They also serve the purpose of managing conflicts between units because they bring accountability to the norms. ‘A polycentricity metanorm relies on covenantal (or similar foundational) orientation that takes the interests and perspectives of others into serious consideration.’52 Metanorms help us understand why a particular system functions the way it does. Malik distinguishes polycentric metanorms, which serve to strengthen polycentric governance, from monocentric metanorms which serve to strengthen a central monolithic authority. Therefore, a polycentric system of governance to function well when the metanorms of the participating individuals and groups are pre-dominantly monocentric.

This means developing polycentric governance in the Wycliffe Global Alliance requires an explicit and intentional commitment, starting with the board and leadership team. The result could create a much more deeply connected and richly diverse environment in the Alliance, where it draws upon and benefits from the knowledge, learning, and problem-solving skills as well as the spirituality embedded in each of the Alliance Organizations. Moving towards a polycentric system of governance in the Alliance will take more hard work and interpersonal/intercultural interaction than we may have realised thus far in our discussions.

In the Alliance’s case, its metanorms are its biblical and missiological foundations that support community, generosity, mutual service, sacrifice for the sake of others, and recognising that the Alliance is a steward of God’s mission. These metanorms are expressed in the Alliance’s Foundational Statements and Philosophy and Principle statements (such as Funding, Community, People, Translation Programs, and Church).

One of Malik’s more sobering observations is how rogue elements within a polycentric system can undermine the good that the rest of the group is seeking to do. Such elements in the Alliance’s case could be organisations that seek to be disruptive to or violate the metanorms in some way. Another example is how more powerful Alliance Organizations may act in a post-colonial mindset with smaller, less powerful ones. This is especially so when there are great differences in power and capacity so that the stronger unit(s) take control. Another example is the display of ideological differences that lead to unnecessarily negative statements about other churches or agencies, or competition among such groups for resources, people, strategies, loyalty, or ministry opportunities. A lot depends on the strength of positive shared metanorms and the civic-mindedness of the participating organisations.

While polycentrism specifically seeks to utilise the local knowledge and problem-solving capabilities of indigenous groups, there can be challenges in incorporating indigenous groups and more mainstream groups. This is especially so because of considerable differences in the way rules and law are understood and carried out:

Indigenous law is flexible, dynamic, and situation-specific rather than providing “a justice ‘product’ that is consistent over time and space” as is the case with Western systems, which are based on written rules and precedent and seek consistent administration of justice across society. In many cases, there is a gap between the central state authority’s focus on individual rights and indigenous emphasis on collective rights 53

Since the Wycliffe Global Alliance serves indigenous communities, Malik’s insights could be helpful especially in the Americas Area as it explores ways to increasingly include such communities in the decision-making process for the Bible translation movement.

Polycentric governance accounts for the resolution of conflicts among participants as part of the process of developing a system that fits the needs of the participants. It downplays the role of out- siders, who don’t know and can’t know all the contextual knowledge that exists among the participating groups. Polycentric governance requires a designated group to be identified who monitor and evaluate whether what is happening is supposed to be happening or not, who have the authority to intervene when the answer is no.

In summary, polycentric governance as described by Malik is not about taking away an autonomous centre and replacing it with multiple autonomous centres but arriving at an understanding of degrees and domains of autonomy that function well together guided by the overarching metanorms.

Deciding Factors

The journey of exploring polycentric governance for the Wycliffe Global Alliance board can be summarised in Table 5:

The Wycliffe Global Alliance board’s discussions of polycentric governance were inconclusive in determining a way forward. It had to consider its legal requirements of being incorporated in the State of Texas. A minimal board structure for legal and financial requirements could have been a possibility. Instead of a board, there could be a ‘wise’ counsel for ongoing giving of input, accountability and direction and provide fresh thinking, appropriate expertise, diversity, and depending on issues, topics and ongoing needs. There could be fluidity on the group of wise counsel with people coming and going depending on the topic and expertise needed.

Latin America Experiment

In 2019, the Wycliffe Global Alliance’s Americas Area team started a ‘Polycentrism Project’ to research the current mental models shaping behaviour and relationships among movements in Latin America. This included the current realities in Bible translation movement in the region that are relevant (to connect the theory and practice of polycentrism to these realities). The team planned to study the concepts of polycentrism, network theory, complexity theory, collaboration, global structures, social movements and differentiating between polycentric governance and other forms of collaboration like networks or alliances.

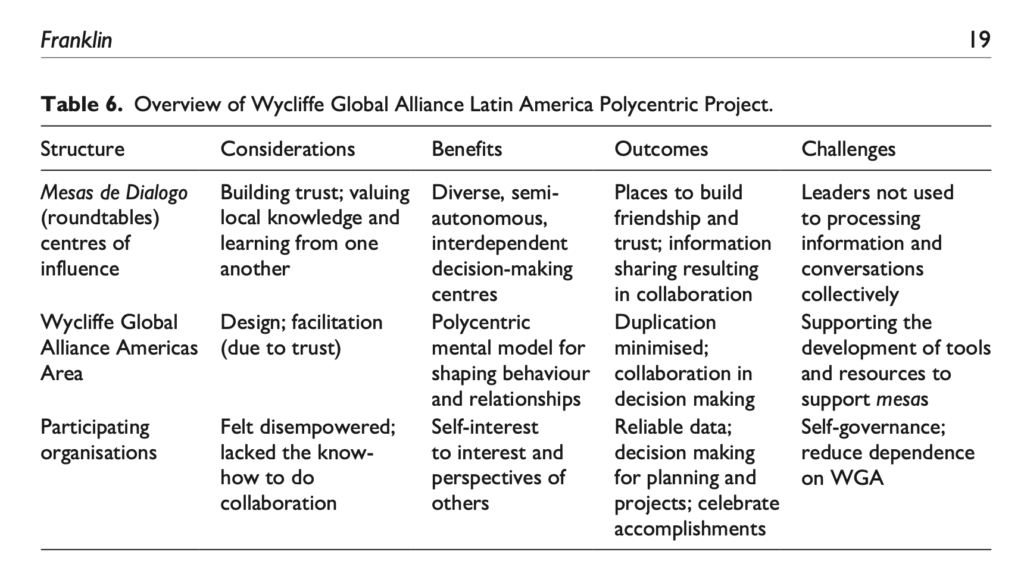

The team set up Mesas de Dialogo (roundtables), which are centres of influence in the countries represented. Area Director and team leader, Nydia Garcia-Schmidt were motivated to head in this direction because she sensed that individual organisational leaders in the regional Bible translation movement did not see themselves having any influence on the local, regional or even global movement and they also did not know how to set up collaborative efforts. Garcia-Schmidt’s role has been to guide the principles that shape and form the initiative while her colleague David Cardenas has been the one setting up the structure and documentation. Together they and their team created criteria for participation in a mesa and how participants are welcomed into the process and community.

Developing the process for the mesas to operate as a polycentric system meant the design team considered the presence of diverse, semi-autonomous and interdependent decision-making centres at multiple over-lapping levels with agreed-upon processes for conflict resolution. There needed to be agreed upon metanorms that covered how the centres took consideration for one another and committed to mutually beneficial influence with an appreciation of the benefits of collective action and taken together, all contribute to creating a self-regulating system.

Each mesa had foundational principles, values and practices that included: moving self-interest to consider the interest and perspectives of others and seeking each other’s mutual benefit; assuming a posture of valuing local knowledge and learning from one another, and appreciating the benefits of taking action together. The mesas have a shared understanding of the situation of Bible translation work in their respective country and a shared understanding of what is happening in other mesas. The Bible translation movement is aware of the mesas that they do and how they function. Each participating ministry and church understand their role as autonomous organisations that have chosen to participate in an inter-dependent way in the mesa and understand what that interdependence involves. Mesas are learning and growing in self-governing practices. Mesas have agreed on processes in place for bringing up and addressing critical issues relevant to their collective ministry. Mesas have reliable data regarding Bible translation which they use to inform their decision-making for improved planning and projects and to celebrate accomplishments. The mesas have developed a simple system of mutual accountability for the collective resources which the group is stewarding. The mesas have developed a low-cost process for engaging in conflict resolution. Together, these all contribute to the building blocks to create self-regulating, self-governing systems.

Various resources are being developed to help the mesas understand their polycentric contribution to the wider movement. This includes webinars and online resources that included one-page reviews and summaries of important books or articles; a library of polycentrism documents; case studies and illustrations; polycentrism occasional bulletin; tools for understanding mental models regarding participating in, and contributing to, global events and structures. There would be cooperation with existing- ing training institutions in developing short courses. The structure would develop a tracking system for mesas to create ongoing ‘snapshots’ to monitor progress and learning because the mesas had the potential to develop into polycentric systems. Eventually, these mesas could participate in global conversations with representatives of the mesas rather than representatives of individual organisations.

Over six months after setting up the first mesas, Garcia-Schmidt believes the initiative is heading in the right direction, but she sees that at the local level, leaders are not used to processing information and conversations collectively. Building trust has to happen first because there has been mistrust or past history that the leaders bring to the mesas. Once trust is built, the leaders see the bigger picture and learn how collaborative efforts will produce a greater impact. A key factor is the role of the Wycliffe Global Alliance as facilitating the mesas. Ministries have trusted the Alliance to set the table and they come and find the space worth the effort to attend. In the spirit of polycentric thinking, Garcia-Schmidt is exploring a way for the mesas to find ways to govern themselves and not become dependent on the Alliance. So far, the mesas have seen these positive results: places to build friendship and trust; information sharing that results naturally in collaboration; places were duplication of efforts in minimised and where collaboration in decision making takes place. Specifically, in the case of Colombia, the mesas there will be making decisions on new starts of Bible translation programs rather than by individual organisations. The mesas are also a platform to engage the church in topics such as generosity and unity and shalom.

The uniqueness of this polycentric approach is summarised in Table 6:

Conclusion

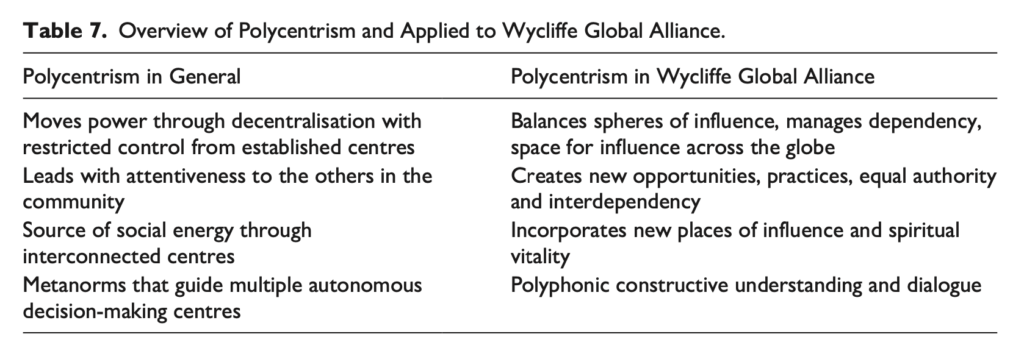

Throughout church history there has been the plurality of centres of the church, cultural expressions of Christianity, confessional variations, and indigenous initiatives. Polycentrism in the church recognises that leadership can come from anyone the Holy Spirit empowers, regardless of age or experience. A formal leadership structure does not necessarily guide the relationship between the leader and the follower. Instead, it is more likely to be the Holy Spirit who does so. Table 7 contrasts general concepts of polycentrism with a specific application within Wycliffe Global Alliance, the subject of this case study:

Through polycentrism, there has been a deliberate movement away from established centres of power, so that leadership occurred among and with others, while creatively learning together in community. Through polycentrism, the historic Western players in Wycliffe Global Alliance have intentionally been opening up structures and processes to give space for the global church and mission community to participate in the Bible translation movement. The Alliance’s missiological perspective comes from many cultural homes within the diversity of cultures that constitute it. Through the missiological influences at a board, leadership team and Alliance organisational level, leaders from across the globe generate new patterns of missiological influence to the Alliance. The arising missiology will enable the Alliance and all its leaders and organisations to be better prepared to face the challenge of global mission. It follows that, for a mission to be global and not owned by only one region, polycentric missiological discussions should be a standard and not optional.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Kirk Franklin https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4505-0557

Notes

* This paper was presented at the OCMS Montagu Barker Lecture Series: ‘Polycentric Theology, Mission, and Mission Leadership’, on 15 September 2020.

- Stephen Neill, Creative Tension: The Duff Lectures (London: Edinburgh House Press, 1959), 81.

- Robert Yin, Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, Sixth ed. (Thousand Oaks: SAGE, 2018), Loc 722.

- Yin, Loc 1671.

- Kirk Franklin, “A Paradigm for Global Mission Leadership: The Journey of the Wycliffe Global Alliance” (University of Pretoria, 2016), 211.

- Susan Van Wynen, Dave Crough, and Kirk Franklin, “Foundational Statements of the Wycliffe Global Alliance,” 2019, accessed 7 September, 2020, https://www.wycliffe.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/ Alliance_Foundational_Statements_2019_09_EN.pdf.

- Philip Harris, Robert Moran, and Sarah Moran, Managing Cultural Differences: Global Leadership Strategies for the Twenty-First Century (Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004), 28-29.

- Daryl Balia, and Kirsteen Kim, Witnessing to Christ Today, vol. Two, Edinburgh 2010 (Oxford: Regnum, 2010), Series Preface, n.p.

- Balia, and Kim, 165.

- Balia, and Kim, 255.

- Charles Van Engen, Transforming Mission Theology (Pasadena: William Carey Library, 2017), 25.

- Barnabe Assohoto, and Samuel Ngewa, “Genesis,” in Africa Bible Commentary, ed. Tokunboh Adeyemo (Nairobi: WordAlive Publishers, 2006), 27.

- N. T. Wright, Paul: A Biography (New York: HarperCollins, 2018), 10.

- Eckhard Schnabel, Paul the Missionary: Realities, Strategies and Methods (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2008), 288.

- Schnabel, 317.

- Quoted in Van Engen, 2017, 68.

- Van Engen, 2006, 174.

- Van Engen, 2006, 173.

- Charles Van Engen, “The Local Church: Locality and Catholicity in a Globalizing World,” in Globalizing Thology: Belief and Practice in an Era of World Christianity, ed. Craig Ott and Harold Netland (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006), 172.

- Tite Tinéou, “Christian Theology in the Era of World Christianity,” ed. Craig Ott and Harold Netland (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006), 38.

- Kirsteen Kim, Joining in with the Spirit: Connecting World Church and Local Mission (London: Epworth, 2009), 15.

- JR Woodward, Creating a Missional Culture: Equipping the Church for the Sake of the World (Downers Grove: IVP Books, 2012), 60.

- Suzanne Morse, “Five Building Blocks for Successful Communities,” in The Community of the Future, ed. Frances Hesselbein et al. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1998), 234.

- Lamin Sanneh, Translating the Message (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1989), 51.

- Philip Smith, “Perspectives of Global Leaders on the Future of Multiethnic Collaboration: An Exploration” (Major Project, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, 2020), 7.

- Kim, 16.

- WBTI, “Extracts of Minutes of Board of Directors Meeting,” November 2003.

- Van Wynen, Crough, and Franklin.

- Van Wynen, Crough, and Franklin.

- Van Wynen, Crough, and Franklin.

- David Bosch, Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2011), 501.

- Van Wynen, Crough, and Franklin.

- Van Wynen, Crough, and Franklin.

- Christina Walker, “Inclusive Leadership in Ingo, Multinational Teams: Learning, Listening and Voicing in ‘Attentive Space’” (Trinity International University, 2020), 69.

- Walker, 67.

- Walker, 91.

- Walker, 67.

- Walker, 32.

- Kirk Franklin, and Nelus Niemandt, “Funding God’s Mission: Towards a Missiology of Generosity,” Missionalia 43, no. 3 (2015): 398, https://dx.doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.7832/43-3-98.

- Dachollom Datiri, “1 Corinthians,” in Africa Bible Commentary, ed. Tokunboh Adeyemo (Nairobi: WordAlive Publishers, 2006), 1393.

- Keith Carlisle, and Rebecca Gruby, “Polycentric Systems of Governance: A Theoretical Model for the Commons,” Policy Studies Journal 47, no. 4 (2019): 927.

- Carlisle, and Gruby 932.

- Carlisle, and Gruby 934.

- Carlisle, and Gruby 933.

- Carlisle, and Gruby 928.

- Carlisle, and Gruby 939.

- Carlisle, and Gruby 939.

- Anas Malik, Polycentricity, Islam, and Development (Lanham: Lexington Press, 2018), 19.

- Malik, 53.

- Malik, 55.

- Malik, 19.

- Malik, 88.

- Malik, 272.

- Malik, 85.

References

Assohoto B and Ngewa S (2006) Genesis. In: Adeyemo T (ed.), Africa Bible Commentary. Nairobi: WordAlive Publishers.

Balia D and Kim K (2010) Witnessing to Christ Today. vol. 2. Edinburgh 2010. Oxford: Regnum.

Bosch D (2011) Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. Carlisle K and Gruby R (2019) Polycentric systems of governance: a theoretical model for the commons.

Policy Studies Journal 47(4): 927–952.

Datiri D (2006) 1 Corinthians. In: Adeyemo T (ed.), Africa Bible Commentary. Nairobi: WordAlive Publishers. Franklin K (2016) A Paradigm for Global Mission Leadership: The Journey of the Wycliffe Global Alliance.

South Africa: University of Pretoria.

Franklin K and Niemandt N (2015) Funding god’s mission: towards a missiology of generosity. Missionalia

43(3):: 384-409. https://dx.doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.7832/43-3-98.

Harris P, Moran R and Moran S (2004) Managing Cultural Differences: Global Leadership Strategies for the

Twenty-First Century. Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

Kim K (2009) Joining in with the Spirit: Connecting World Church and Local Mission. London: Epworth. Malik A (2018) Polycentricity, Islam, and Development. Lanham: Lexington Press.

Morse S (1998) Five building blocks for successful communities. In: Hesselbein F, Goldsmith M and

Beckhard R (eds), The Community of the Future. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Neill S (1959) Creative Tension: The Duff Lectures. London: Edinburgh House Press.

Sanneh L (1989) Translating the Message. Maryknoll: Orbis Books.

Schnabel E (2008) Paul the Missionary: Realities, Strategies and Methods. Downers Grove: IVP Academic. Smith P (2020) Perspectives of Global Leaders on the Future of Multiethnic Collaboration: An Exploration.

Major Project, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School.

Tinéou T (2006) Christian Theology in the Era of World Christianity. Edited by Ott C and Netland H. Grand

Rapids: Baker Academic.

Van Engen C (2006) The local church: locality and catholicity in a globalizing world. In: Ott C and Netland

H (eds) Globalizing Thology: Belief and Practice in an Era of World Christianity. Grand Rapids: Baker

Academic, 2006.

Van Engen C (2017) Transforming Mission Theology. Pasadena: William Carey Library, 2017.

Van Wynen S, Crough D and Franklin K (2019) Foundational statements of the wycliffe global alliance. Available

at: https://www.wycliffe.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Alliance_Foundational_Statements_2019_09_

EN.pdf. Accessed 7 September 2020.

Walker C (2020) Inclusive Leadership in Ingo, Multinational Teams: Learning, Listening and Voicing in

‘Attentive Space’. Chicago: Trinity International University, 2020.

WBTI. (2003) Extracts of Minutes of Board of Directors Meeting. November.

Woodward JR (2012) Creating a Missional Culture: Equipping the Church for the Sake of the World.

Downers Grove: IVP Books.

Wright NT (2018) Paul: A Biography. New York: HarperCollins.

Yin R (2018) Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th Edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Author Biography

Kirk Franklin is associate faculty of Global Missional Leadership at OCMS, Director of the Centre for Missional Engagement at Melbourne School of Theology, Australia, and researcher in global leadership. He has earlier served as Executive Director of Wycliffe Global Alliance and of Wycliffe Australia. He was born and raised in Papua New Guinea where he also served as a missionary. He is author of Towards Global Missional Leadership (Regnum).

More Information

This paper was originally published in OCMS and is used here with their permission.