Joseph W. Handley, Jr.

Published in Global Missiology, www.globalmissiology.org, April 2022

Abstract

One of the simplest definitions for a Kingdom Movement is that proposed by David Garrison in looking at Church Planting Movements: “a rapid multiplication of indigenous churches planting churches that sweeps through a people group or population segment” (Garrison 2004, 21). Over the years, the terminology has changed but in essence Garrison’s definition captures the basic construct of these types of movements. The growth of literature about how these movements flourish is remarkable (Cole 2020; Lim 2017). While leadership approaches are reflected in these studies, the focus could be strengthened. In addition, while general missional leadership theories relate, they do not necessarily bring full attention to leading these types of multiplying movements. Perhaps the closest approach would be Mike Breen’s book Leading Kingdom Movements. He posits a biblical framework for disciple making encouraging leaders to invest in others by expanding their scope of influence — but still more can be explored (Breen 2015).

This article draws on recent research on Polycentric Mission Leadership highlighting an approach worth further contemplation and study (Handley 2018; 2020). The research conveyed in the article unfolds with movement theory, a “team of teams” construct, collaboration and partnership, CUBE theory and systems leadership, and targeted interviews. Ultimately, polycentric leadership is offered as a new theoretical model for leadership. Polycentric leadership is a collaborative, communal approach to leadership that empowers multiple centers of influence as well as a diverse array of leaders. The article claims that polycentric leadership is well suited to addressing contemporary issues and to leading Kingdom Movements during this era of a globalization.

Key Words: collaboration, Lausanne Movement, leadership, movements, partnership, polycentricity

Cube Theory and Systems Leadership

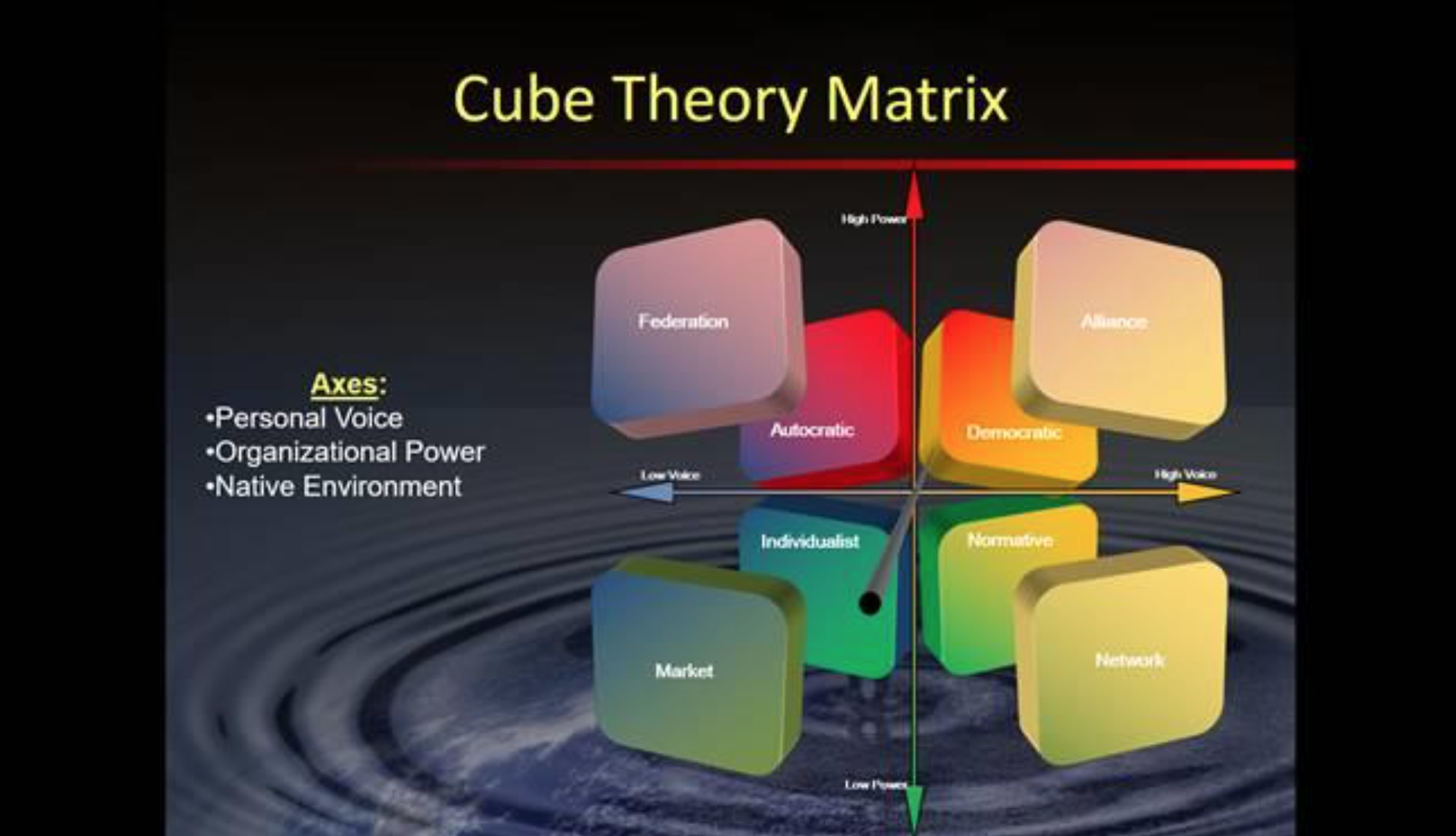

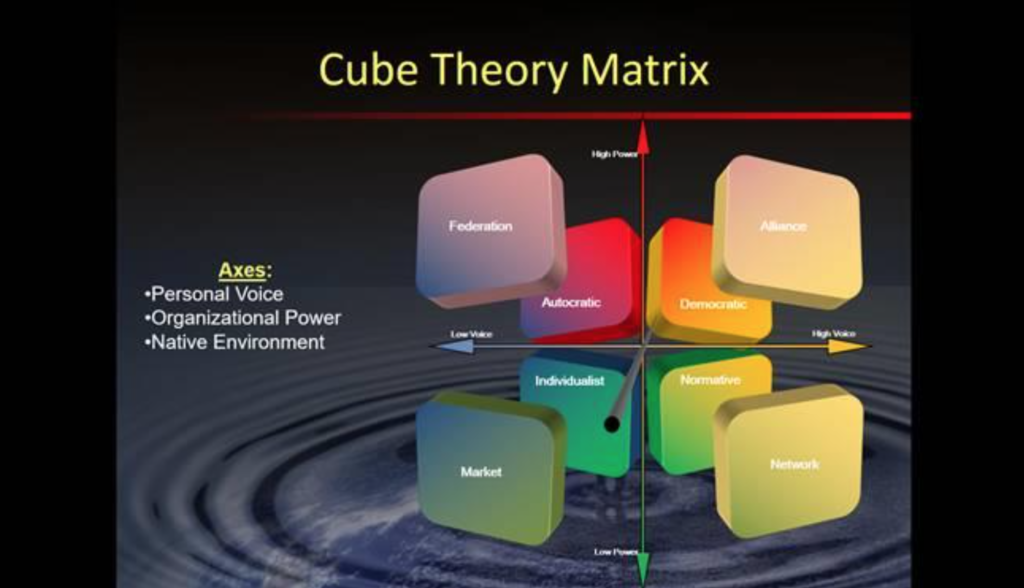

Another lens through which we can view how Kingdom Movements are led is found in Mark Avery’s research, Beyond Interdependency: An identity-based perspective on interorganizational mission (see Avery’s Cube Theory Matrix in Figure 1 below). Avery’s study found that a critical factor to effective interorganizational leadership was governance across multiple organizations. As agencies worked together, oftentimes the key was how they coordinated their efforts (Avery 2005, 79). Avery states that “the [CUBE Theory] model provides a coherent language for analyzing eight distinct coordination schemes along (at least) three generic axes” (Avery 2005, 96).

Avery hoped that his model would be taken up by other researchers to strengthen the theory and advance the idea of multi-agency coordination. In a personal interview with him, he mentioned to me that the model is simply a grid-group model of communication across different cultures. “Partnership is the solution to a problem many people don’t feel or don’t have. [It] helps transform the process rather than a cause [and is] much more about shared responsibility about how things work in a particular context” (Avery 2016). This perspective flows well with what McChrystal discovered during his time in the military. In essence, the work of the U.S. military in fighting Al Qaeda involved an intra-group engagement. A variety of government agencies worked alongside a number of military units and divisions. In order to work together effectively, they had to lower efficiency. Avery reviewed three perspectives on organizational leadership to develop his Cube Theory. The first was that of Scharpf and the Negotiated self-organization. He contrasted that with Rhodes’ Socio-Cybernetic Systems and Hajer and Wagenaar’s view of Networks. From these primary sources, he discovered four incidental axes:

• Market vs. Democratic Hierarchy

• Network vs. Autocratic

• Communal Norms vs. Tasks Interdependence

• Individualist vs. Federal (Avery 2005, 88)

Avery describes the key finding for leading Kingdom Movements as “A network … a high voice, low power, adaptive form native to an extra group environment. Social norms, absence of formalized boundaries, voluntary involvement, and centrality of trust are some characteristic factors of this scheme of coordination” (Avery 2005, 98). This idea of movement leadership in an age of networks (as shown through Esler in movement leadership and McChrystal through the lens of military leadership) is pivotal for leadership in a global era.

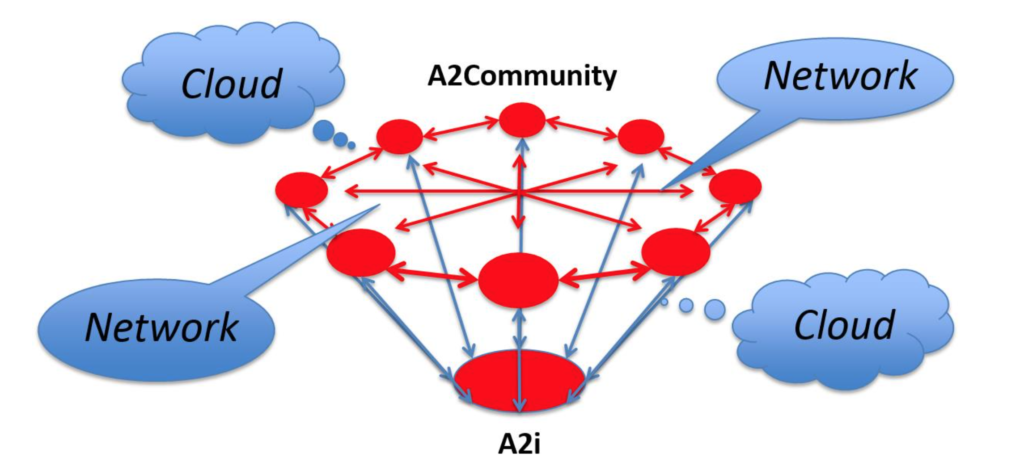

A3, the mission I lead, has done initial research in this arena. Our work is more movement oriented than organizational in nature. In advising us, Kn Moy contrasted the differences between the Arab Spring and Al Qaeda. Both were powerful movements led predominantly by volunteer forces. The key difference between the short-lived Arab Spring and the sustained movement of Al Qaeda involved Al Qaeda having a small core at its center who were the keepers of the vision, mission, and values. Moy went on to suggest that A3 was more illustrative of movements than of traditional mission organizations (Snuggs 2015). To gain insight into how CUBE Theory might operate within a networked organization, Snuggs used the model below from Takeshi Takazawa (see Figure 2). This is a model that is polycentric in function. Rather than having a point or lead person directing the ship, it relies on the system in dynamic interplay. The center or core holds the framework together with the vision, mission, and values, but all else operates rather freely within the network. As the community extends it influences movements beyond the organizational structure. Leaders move in and out of the core depending on their focus, but the influence extends rather broadly. Given that the A3 Community is a network of pastors, NGO leaders, and business executives from several nations, communication practices have to adapt based on the different cultures and leadership ideals of each country. Similarities are consistent within regions (East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia), but even within those regions the differences to which Avery points are apparent. Add to this the global body of Christ interacting with each of these members of the A3 Community, and the complexity becomes enormous.

Editor’s note: “A3” used to be known as “A2”

Taking this idea further, Snuggs speaks about leadership within a system, using Wikipedia as an example:

Wikipedia is a nonprofit organization that has become the go-to place for information on

just about every topic there is. It is actually a movement. Anyone can be a part of Wikipedia

as a user of the information or a creator of content. But there are values and ensuing ‘rules’

that a core of people ruthlessly enforce. And many people who do this are not paid staff.

They are a very small percentage of the Wikipedia movement who spend a huge amount

of their time editing and reviewing entries. They do it because they are committed to the

vision, mission and values of Wikipedia. They are a part of the core which keeps Wikipedia

relevant. And they are enhanced by organizational-like units of paid staff. There is no

directory that will tell us who is in the core of Wikipedia. There probably is a directory of

staff, board members, etc. And there probably is some sort of an org chart for them. Some

in that directory or on that chart will of course be core to Wikipedia. But being on staff

does not make them core any more than being a volunteer excludes someone from the core

(Snuggs 2015).

Brook Manville in Harvard Business Review highlights a deeper insight that a community becomes even more pertinent than the network:

A big goal requires a ‘thick we network—a community of people who feel responsible for collaborating toward a shared purpose that they see as superseding their individual needs. Members of a community—as opposed to a simple network—expect relationships within the group to continue, and they even hold one another accountable for effort and performance. When networks develop into communities, the results can be powerful (Manville 2014).

Manville maintains that it takes three key factors to foster this type of community. First, the leaders put the groups’ purposes, and the groups themselves, ahead of any one person or goal. Second, they employ inspiration along with action steps to move things forward. Finally, these leaders ensure that the people in the community are the heroes rather than the people at the helm. Manville concludes, “In our emerging super-networked economy, the next-generation leaders will increasingly be mobilizers, not directors. These leaders will define their role not as ‘me’ but ‘we’— and understand that when it comes to ‘we’, the thicker the better” (Manville 2014).

Mike Breen captures this group-first leadership concept from a spiritual perspective, stating, “I can assure you that if you look at the great movements of the past (whether in business, politics, societal change, etc.), what you will find in the middle is a group of people truly living as an extended family” (Breen 2013, 1079). Breen does a masterful job of presenting the simple, reproducible models Jesus embodied as seen in the New Testament. The findings on leading Kingdom Movements dovetail with Jesus’s approach of investing life into a few key disciples and encouraging them to reproduce the dynamism that he gives them in mission. This highlights the communal nature of polycentric leadership. The relationships are deep and strong, holding the community together (Handley 2021, 231, 233).

Wiseman and McKeown capture this leadership style in their book Multipliers. They walk through different types of leaders in various organizations and highlight those who draw out the best in others and foster momentum. These leaders generate “extraordinary results.” They see more in others than in themselves. They may not be the most talented or most gifted individuals, but their knack for empowering others is exponential. “Multipliers lead people by operating as Talent Magnets, whereby they attract and deploy talent to its fullest regardless of who owns the resource. People flock to work with them directly or otherwise because they know they will grow and be successful” (Wisemen and KcKeown 2010, 415).

IBM’s Center for the Business of Government notes some of these attributes in their studies of networks and leadership as well. Leadership in a network is not viewed as the purview of a single leader in a formal leadership position, but it is rather seen as something more organic in nature that is supported and grown across the network. This way of conceptualizing leadership aligns with both a relational view of leadership that focuses on process, context, and relationship building as well as with the literature on complexity leadership, where leadership processes can be shared, distributed, collective, relational, dynamic, emergent, and adaptive. The role of a network manager as leader is to nurture this kind of leadership. Some terms used to describe network leadership include host, servant leader, helper, network weaver, and network orchestrator. However, some types of networks, such as mandated networks, may need to approximate more traditional forms of leadership (Popp et al. 2014).

Peter Senge, along with colleagues Hamilton and Kania, explored these ideas further. They point to the groundbreaking work of Ronald Heifetz on adaptive leadership and the importance of collective thinking. They advocate for a new type of leadership that they call systems leadership. They describe systems leadership in terms that encapsulate much of what I have been studying this last decade on global leadership:

[Systems leaders have the] ability to see reality through the eyes of people very different from themselves…. They build relationships based on deep listening, and networks of trust and collaboration start to flourish. They are so convinced that something can be done that they do not wait for a fully developed plan, thereby freeing others to step ahead and learn by doing. Indeed, one of their greatest contributions can come from the strength of their ignorance, which gives them permission to ask obvious questions and to embody an openness and commitment to their own ongoing learning and growth that eventually infuse larger change efforts (Senge et al. 2015, 3-4).

The way that systems leadership flows dovetails well with leading Kingdom Movements. It is in this type of ecosystem where leaders thrive, feeling the freedom to work entrepreneurially with the support of the family. In this polycentric system, collaboration thrives and relies on every facet of the company or organization, empowering the full diversity of its membership and connectivity (Handley 2021, 232).

Interviews with Lausanne Movement Leaders

To verify these findings, I conducted and analyzed interviews with Lausanne Movement leaders to discern key issues, trends, and challenges they face, how they have grown and been formed as leaders, and how leadership has changed in the past 20 years. Each of these leaders was chosen for either their effectiveness in leading a current network or the promise they show in getting their networks established. I selected 33 key leaders (representing a variety of ages, genders, countries, cultures, and denominations) who are leading significant initiatives and movements for the Kingdom of God. I visited and interviewed them using Appreciative Inquiry, since some of the leaders were from shame/honor cultures (Shaw, Fuller Seminary, 2012). Appreciative Inquiry uses a positive approach to interviews.

In analyzing the common features, I found that some factors pointed to leadership aspects that are timeless. Long-standing leadership traits included spiritual aspects of missional leadership: being biblically formed, character formation, and Christ-like servanthood. Faithfulness and humility were also deeply interwoven into this thread of spirituality.

The primacy of this spirituality factor was significant. Every leader pointed to a common thread in their life story—of how God clearly intervened and called them to ministry. Over and above this aspect of calling was a deep sense of the need for the Lord’s presence to enable them to serve the way in which they serve. Spradlin mentioned the crucial importance of a “private, personal and intimate worship of the Lord as being priority number one…, [further stating that] powerful public ministry comes from a passionate, private worship walk with the Lord” (Spradlin 2014). Joy Tira stated, “The Church is yearning for this type of intimacy” (Tira 2014).

The common issues driving the need for changes in leadership showed themselves in the following themes: globalization, economic disparity, migration, and technological advancement were all issues leaders identified as requiring changing forms of leadership. The interviewees also discussed moving away from a broad vision toward a more clearly defined set of outcomes, complete with measurable qualities, as being important in the current era.

Tunehag saw a key point that deeply fits the Lausanne ethos as key for leaders today: “To be like Jesus, who constantly and consistently met the needs of the people who came to him. And most came with physical needs, or with social, legal, or economic issues. Jesus never told anyone they had the wrong kind of need. He met their needs, broadened their horizons, and demonstrated the Kingdom of God” (Tunehag 2014).

The changing leadership environment pointed toward further collaboration and teamwork in a society that is significantly impacted by diversity and cross-cultural engagement. The need for more strategic and directional leadership and less sweeping global vision was apparent as well. Along these lines, Smith highlighted the importance of gift-based leadership rather than traitbased leadership. He felt that moving away from the more trait-oriented approaches is critical to faithful, missional leadership today and into the future. He also characterized the leadership changes needed in this manner: “[Leadership is] much more dispersed and distributed (not management by objective). [We need a] vision and values approach—not [simply] by goals and objectives” (Smith 2014).

The relational theme was strong in all of the interviews, especially highlighting an increased need for cross-cultural engagement and collaboration. The sense that vision should emerge from the group more than from an individual, and that people should be empowered, was apparent. As Smith suggested, “giving away power” is critical to success in this age. Talking about ownership, he stated, “The ownership—confidence of indigenous leaders to lead their own way and let westerners get out of the way [will be key for leaders of the future]” (Smith 2014).

Augmenting this relational theme was the importance of possessing cross-cultural leadership skills. Several interviewees expressed this need, saying the Lausanne Movement as a whole could grow in this area. Chiang offered an insightful statement, especially given contexts of honor/shame cultures: “We have neglected the honor/shame perspective so deeply that we don’t know how to regain it. Our theological basis is so shallow that we need to redevelop it” (Chiang 2014).

The final common thread I sensed among these interviews was a need for further creativity and innovation as we look to the future of mission. Whether it was a conversation about technology, the diversity of the world, communication patterns, or something else, there seemed to be a sense that creativity will be crucial for leaders in the future. As Zaretsky said, “[We are] constantly looking for innovative ways to engage around spiritual issues and lots of interesting methodologies in our network” (Zaretsky 2014).

Spradlin captured most of these common threads in one single statement: “[We need] more emphasis on relationship, collaboration, prayer and listening to the Lord, and experimentation” (Spradlin 2014).

Toward a New Theoretical Model for Kingdom Movements: Polycentric Leadership

As we look at leading Kingdom Movements, polycentric traits become apparent. Clearly, leading movements requires a set of skills different than those needed in past generations. The war on terror provided compelling evidence of this need for new leadership skills. The future of leadership is so dynamic, so complex, and so complicated that the simple and efficient structures and systems of the past won’t prove successful. We need a new understanding of leadership for the future that addresses the increased complexities. Leading Kingdom Movements differs from leading in other settings. While a catalytic person or event may provide the key launching point, a movement sustainable for the long term is led by a multiplicity of leaders. These leaders cast vision and mobilize others through simple actionable steps without falling to micromanagement. Bricolage systems, or a collaboration of multiple networks, institutions, and organizations, are at the core of a flourishing movement. And the importance of cultural and cross-cultural acumen in leading networks is paramount if a movement is to thrive.

This article’s research on polycentrism noted the need for more than just a CEO and leadership team. As the title of McChrystal’s book captures, a team of teams, built on enduring relationships and grounded on a foundation of deep trust, makes a network or movement strong. Speed and the ability to pivot on a moment’s notice are paramount. Adaptive leadership is crucial. The team of teams must empower others more than themselves, encourage information sharing, and decentralize authority to the ground levels. Seeking to make a difference in this complex ecosystem requires that leaders work together. Leading collaboratively and in partnership requires similar skills to leading teams of teams or movements. The ability to rally people and groups around purpose and vision is critical to leading well. Building deep relational ties and developing trust binds movements and teams together.

Listening to the network and movement leaders is vital, since listening makes the team feel not only heard but also valued. The role of facilitation is also highlighted in the literature. Facilitating others enables leaders to influence rather than directing toward an organizational objective. Butler emphasized the spiritual dynamic, noting the importance of prayer. Religious movements are not solely understood through social movement theory. Social movements tend to rise due to a problem, whereas spiritual movements are motivated by a higher calling.

Finally, Avery highlighted the systems necessary to catalyze movements and help them thrive. His masterful look at grid-group theory and building the CUBE theory as a model for governance 28 Global Missiology – ISSN 2831-4751 – Vol 19, No 2 (2022) April was exceptional. Ultimately, he determined that the key to leading a movement came down to a network form of leadership. These forms include high voice and low power. Supplementing Avery’s model was the importance of a community rather than a network. Breen pointed out that this community is better seen as a family, especially in the spiritual space. For a movement to thrive, it needs a community that operates from the power of ‘we’ rather than ‘me’ or ‘I’. It is in this more systems model of leadership structure that Kingdom Movements find their sustenance and influence.

Herein lies a more comprehensive model of leadership for the global era. Kingdom Movements involve all of these traits (Charismatic, Collaborative, Communal, Relational, Entrepreneurial, and Diverse) and move away from centralized forms of leadership. These same themes arose in interviews with Lausanne Movement leaders as they expounded on how the movement and leadership have changed over the past 15-20 years. These changes require a new theoretical model of leadership: a polycentric form of leadership.

References (includes references for Part I)

Addison, Steve, Hirsch, Alan, and Roberts, Bob, Jr. (2011). Movements That Change the World:

Five Keys to Spreading the Gospel. Rev. ed. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books.

Addison, Steve (2015). Pioneering Movements: Leadership That Multiplies Disciples and

Churches. IVP Books.

Alire, Camila A. (2001). “Diversity and Leadership” Journal of Liberty Administration 32, 3-4:

99-114. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1300/J111v32n03_07 (accessed January 28,

2022).

Avery, Mark (2005). “Beyond Interdependency: An identity-based perspective on cooperative

interorganizational mission.” PhD Dissertation, Fuller Theological Seminary, School of

Intercultural Studies.

Avery, Mark (2016). Interview via Skype.

Bainbridge, William Sims (1996). The Sociology of Religious Movements. 1st ed. New York:

Routledge.

Birdsall, S. Douglas (2012). “Conflict and Collaboration: a narrative history and analysis of the

interface between the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization and the World

Evangelical Fellowship, the International Fellowship of Evangelical Mission Theologians, and

the AD 2000 movement.” PhD Dissertation, Oxford Centre for Mission Studies.

Blumer, Herbert (1969). Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Upper Saddle River,

NJ: Prentice Hall.

Brafman, Ori, and Beckstrom, Rod A. (2006). The Starfish and the Spider: The Unstoppable

Power of Leaderless Organizations. Reprint ed. New York; London: Portfolio.

Breen, Mike (2013). Leading Kingdom Movements. 3DM.

Butler, Phill (2006). Well Connected: Releasing Power, Restoring Hope through Kingdom

Partnerships. Waynesboro, GA: Authentic. 29

Caligiuri, Paula (2013). “Developing Culturally Agile Global Business Leaders” Organizational

Dynamics July, 42, 3: 175-182.

Chiang, Samuel (2014). Lausanne Catalyst for Orality. June 5 Interview in Manhattan Beach, CA.

Cole, Neil (2020). “Essential Qualities of a Multiplication Movement” Mission Frontiers

September-October, http://www.missionfrontiers.org/issue/article/essential-qualities-of-amultiplication-movement (accessed January 20, 2022).

Coutu, Diane (2009). “Why Teams Don’t Work” Harvard Business Review

https://hbrorg/2009/05/why-teams-don’t-work (accessed January 21, 2022).

Esler, Ted (2012). “Movements and Missionary Agencies: A Case Study of Church Planting

Missionary Teams.” PhD Dissertation, Fuller Theological Seminary, School of Intercultural

Studies.

Garrison, David (2004). Church Planting Movements: How God Is Redeeming a Lost World.

Arkadelphia, AR: WIGTake Resources LLC.

Hanciles, Jehu J. (2009). Beyond Christendom: Globalization, African Migration, and the

Transformation of the West. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books.

Handley, Joseph W. (2018). “Leading Mission Movements” EMQ 54(2): 20-27,

https://www.academic.edu/36615149/Leading_Mission_Movements_EMQ_54_2_2018

(accessed January 21, 2022).

_ (2020). “Polycentric Mission Leadership.” PhD Dissertation, Fuller Theological Seminary, School of Intercultural Studies: ProQuest; 27745033.

_ (2021).“Polycentric mission leadership: Toward a new theoretical model” Transformation 38(3), https://doi.org/10/1177/02653788211025065 (accessed January 20, 2022).

Hesselgrave, David F., McGavran, Donald, and Reed, Jeff (2000). Planting Churches CrossCulturally: North America and Beyond. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

Jopling, Michael and Crandall, David (2006). “Leadership in Networks: Patterns and Practices”

National College for School Leadership, https://www.academia.edu/1763822/Leadership_in_networks_patterns_and_practices

(accessed January 20, 2022).

Kellerman, Barbara. (2012). The End of Leadership. New York: HarperBusiness.Lederleitner, M.

(2009). “Is it possible to adhere to Western ethical and cultural standards regarding financial

accountability without fostering neo-colonialism in this next era of global mission

partnerships? Thoughts and reflections for broader dialogue.” Unpublished paper.

Lim, David (2017). “God’s Kingdom as Oikos Church Networks: A Biblical Theology”

International Journal of Frontier Mission 34:1-4: 25-35,

https://www.ijfm.org/PDFs_IJFM/34_1-4_PDFs/IJFM_34_1-4-Lim.pdf (accessed January

21, 2022).

Lipman-Blumen, Jean. (2000). Connective Leadership: Managing in a Changing World. 1 edition.

Oxford England; New York: Oxford University Press.30

Logan, Dave, King, John, and Fischer-Wright, Halee (2011). Tribal Leadership: Leveraging

Natural Groups to Build a Thriving Organization. Reprint ed. New York: HarperBusiness.

Manville, Brook (2014). “You Need a Community, Not a Network” Harvard Business Review

September 15, https://hbr.org/2014/09/you-need-a-community-not-a-network (accessed

March 25, 2022).

McChrystal, General Stanley, with Tantum Collins, David Silverman, and Chris Fussell (2015).

Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. New York, New York:

Portfolio / Penguin.

Oxbrow, Mark (2010). “Better together: Partnership and collaboration in mission” Edinburgh 2010 Study Theme: Forms of Missionary Engagement.

http://www.edinburgh2010.org/fileadmin/files/edinburgh2010/files/docs/Partnership%20.doc

(accessed January 20, 2022).

Pierson, Paul E. (2009). The Dynamics of Christian Mission: History through a Missiological

Perspective. William Carey International University Press.

Popp, Janice, Milward, H. Brinton, MacKean, Gail, Casebeer, Ann, and Lindstrom, Ronald

(2014). Inter-Organizational Networks: A Review of the Literature to Inform Practice. IBM

Center for The Business of Government.

Primuth, Karin Butler (2015). “Mission Networks: Connecting the Global Church” EMQ

https://synergycommons.net/resources/mission-networks-connecting-the-global-church/

(accessed January 20, 2022).

Schein, Edgar H. (1985). Organizational Culture and Leadership. 1st ed. San Franciso: JosseyBass Publishers.

Senge, Peter, Hamilton, Hal, and Kania, John (2015). “The Dawn of System Leadership” Harvard

Business Review Winter.

Shaw, Dan (2012). “Appreciative Enquiry” lecture, Methods of Interpreting Culture course, Fuller

Theological Seminary.

Sinek, Simon (2011). Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action.

Reprint edition. New York: Portfolio.

Smith, Brad (2014). Cape Town 2010 Table Talk Designer. December 1 Interview via Skype.

Snuggs, Elliott (2015). “A2community.net -– Core -– Network -– Cloud (Overview)” A3 internal website.

Spradlin, Byron (2014). Lausanne Catalyst for the Arts. December 15 Interview via Skype.

Tira, Sadiri Joy (2014). Lausanne Global Diaspora Network. December 6 Interview via Skype.

Transform World Staff (2015). “Transform World: A Starfish Structure” Mission Frontiers MayJune, http://www.missionfrontiers.org/issue/article/transform-world-a-starfish-structure

(accessed January 20, 2022).

Tunehag, Mat (2014). Lausanne Catalyst for Business as Mission. December 4 Interview via

31 Skype

Wei-Skillern, Jane, Ehrlichman, David, and Sawyer, David (2016). “The Most Impactful Leaders

You’ve Never Heard Of” Stanford Social Innovation Review,

http://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_most_impactful_leaders_youve_never_heard_of (accessed

January 20, 2022).

Wiseman, Liz, and McKeown, Greg (2010). Multipliers: How the Best Leaders Make Everyone

Smarter. 1st ed. HarperCollins e-books.

Zaretsky, Tuvya (2014). Lausanne Catalyst for Jewish Evangelism. December 1 Interview via

Skype.

1 Part I was published in the January 2022 Global Missiology issue and can be found at

http://ojs.globalmissiology.org/index.php/english/article/view/2549.

2 In this diagram, A2i refers to Asian Access International leadership serving the movement while A2 community refers to all those who serve within the scope of the vision and mission. Within the movement, there is a network of leaders committed to one another and their common cause. Beyond that, each participant is engaged in activities that

may relate to the mission but may not be something everyone within the movement is committed to. Editor’s Note: Prior to 2023, “A3” used to be known as “A2”.