Case Study: A non-profit mission organization in Japan becomes a global leader development movement

THE CORE–NETWORK–CLOUD MOVEMENT MODEL

INTRODUCTION

Over the past eight years I have been researching various aspects of leadership to gain a deeper understanding of how to lead mission movements within the globalized ecosystem in which we now live. This article presents a new theory on polycentric leadership to help missional leaders effectively traverse this modern landscape. It is based on research meant to review fresh perspectives on mission leadership in a global era. Given that the Lausanne Movement provided a unique ecosystem in which to conduct the experiment, a study of the history of the movement was made, paying keen attention to the last 15 years of dramatic global shifts.

The primary research for this project revolved around four key authors and researchers, augmented by leadership studies from both the mission and business world. The four sections below coincide with each of these key authors and researchers. Finally, after reviewing these ideas, the study concludes with recommendations toward a new model for effective mission leadership in the global era.

Movement theory

The first step in discerning the impact of leadership in missional movements was to gain a greater appreciation for movement theory, with a particular focus on religious (missional) and church movements. The study began with a look at Ted Esler’s research on Movements and Mission Agencies.1 Esler provided an overview of various aspects of movement theory, looking at social, organizational and religious movements.

As Esler looked at the various types of movement theory, he posited a General Integrated Movement Attribute Model which focuses on resource mobilization.2 He states:

Resource mobilization theory suggests that movement organization is a dominant feature of a movement… Understanding the missionary agency as an organization bent on forming religious movements opens up the possibility that organizational theory can be applied to the study of movements.3

In coming to this model of movement theory, Esler looked first at New Social Movements and Social Movement Organizations. He sought wisdom from these models and theories to better understand how church planting teams could be effective. Esler rightly notes that religious movements don’t necessarily form from a position of unrest. He reviewed missiologists like Roland Allen, Donald McGavran and David Garrison. In doing so, he sees an interesting conflict. The observations cited above point to a multiplicity of leaders for a movement, but Paul Pierson suggests that “breakthroughs, expansion, renewal movements and the like are almost always triggered by a key person.”4 Esler suggests that reconciliation may be in the form of the leader purely as a “catalyst or lightning rod” rather than as the sole leader of the movement.5

Another aspect of Esler’s research relates to organizational or movement structures. Esler highlights the work of Campbell in developing a bricolage6 as a fresh way to form these cooperatives. He points to the work of Zed and Asher who say of coalitions, “The coalition pools resources and coordinates plans, while keeping distinct organizational identities.”7

Team of Teams

In 2015, General Stanley McChrystal partnered with researchers from Yale University to study the fight against the Al Qaeda network. McChrystal argues that “to succeed, maybe even to survive, in the new environment, organizations and leaders must fundamentally change. Efficiency, once the sole icon on the hill, must make room for adaptability in structures, processes, and mindsets that is often uncomfortable.”8

According to McChrystal, the U.S. military is the single most efficient, prepared, and powerful force in the world. Yet with all their might and proficiency, they could not defeat the Al Qaeda network: “We were stronger, more efficient, more robust. But AQI was agile and resilient. In complex environments, resilience often spells success, while even the most brilliantly engineered fixed solutions are often insufficient or counterproductive.”9

Many leadership books of past eras highlight the role of the CEO, the pastor, or General Manager. McChrystal states that this type of leadership led to more things being produced in a faster time for less overall cost. However, “This new world [of conflict with Al-Qaeda] required a fundamental rewriting of the rules of the game. In order to win, we would have to set aside many of the lessons that millennia of military procedure and a century of optimized efficiencies had taught us.”10 He adds, “These events and actors were not only more interdependent than in previous wars, they were also faster. The environment was not just complicated, it was complex.”11

McChrystal realized that their leadership needed a new theme: “It Takes a Network to Defeat a Network.”12 He states, “Cooperative adaptability is essential to high-performing teams.”13 McChrystal argues that a more decentralized structure is better designed for this type of warfare: “Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ of the market—the notion that order best arises not from centralized design but through the decentralized interactivity of buyers and sellers—is an example of ‘emergence’. In other words, order can emerge from the bottom up, as opposed to being directed, with a plan, from the top down.”14

Given these new realities, the military instituted a systems form of thinking where information was shared broadly. It was less efficient, but it created holistic awareness and allowed them to operate as a team of teams. McChrystal cites the research of Sandy Pentland from MIT, who found that “sharing information and creating strong horizontal relationships improves the effectiveness.”15 McChrystal concludes with insights on wisdom for leadership in a complex era:

Effective adaptation to emerging threats and opportunities requires the disciplined practice of empowered execution. Individuals and teams closest to the problem, armed with unprecedented levels of insights from across the network, offer the best ability to decide and act decisively… The doctrine of empowered execution may at first glance seem to suggest that leaders are no longer needed. That is certainly the connection made by many who have described networks such as AQI as “leaderless.” But this is wrong. Without Zarqawi, AQI would have been an entirely different organization. In fact, due to the leverage leaders can harness through technology and managerial practices like shared consciousness and empowered execution, senior leaders are now more important than ever, but the role is very different from that of the traditional heroic decision maker.16

Collaboration and partnership

In Phill Butler’s book Well Connected, Butler points out that what attracts people and keeps them committed to a partnership are 1) great vision and 2) seeing results.17 According to Butler, once you have a compelling reason to work together and a desire for strong results, you must then build trust. “All durable, effective partnerships are built on trust and whole relationships.”18 There must be trust between the people, the processes and the plans for effective partnership to develop. Leading a movement is significantly different from leading a company that doesn’t have a lot of stakeholders. It’s similar, perhaps, to leading a modern university. Butler emphasizes:

Spiritual breakthroughs are not a game of guns and money. No human effort, expenditure of resources, or brilliant strategy will alone produce lasting spiritual change. Our partnerships must be informed and empowered by God’s Holy Spirit in order to be effective. The challenges of relationships, cultural and theological differences, technical and strategic issues, and sustainability can only be dealt with in a process rooted in prayer.19

Butler also highlights practical considerations for managing the actual partnership: Developing clear and measurable goals, setting a realistic time frame for action, putting in place sustainable personnel to see the project through, and fostering ownership of the vision that grows over time.20

visionSynergy CEO Kärin Primuth, in a recent article in Evangelical Missions Quarterly, points to movements in the Muslim world that began with Western leaders now being led by indigenous leaders. Primuth notes that these multi-cultural networks are a demonstration of biblical unity:

Networks offer a context to build trust across cultures and to genuinely listen and learn from our partners in the Majority World. They provide a platform for dialogue with our brothers and sisters in the Global South to mutually define what the North American Church can contribute to today’s mission movement.21

Cube theory and systems of leadership In Mark Avery’s dissertation Beyond Interdependency: An identity based perspective on interorganizational mission, Avery found that a critical factor to effective interorganizational leadership was governance across multiple organizations. As agencies worked together, the key was how they coordinated their efforts.22 Avery states that “the [CUBE Theory] model provides a coherent language for analyzing eight distinct coordination schemes along (at least) three generic axes.”23

Figure 1 – CUBE THEORY (from Mark Avery)

In a personal interview, Avery told me that the model is simply a grid-group model of communication across different cultures.24 “Partnership is the solution to a problem many people don’t feel or don’t have. [It] helps transform the process rather than a cause [and is] much more about shared responsibility about how things work in a particular context.”25

Avery describes the key finding for leading movements as “A network…a high voice, low power, adaptive form native to an extra group environment. Social norms, absence of formalized boundaries, voluntary involvement, and centrality of trust are some characteristic factors of this scheme of coordination.”26

A3 (formerly Asian Access) has done initial research in this area. Executive Vice President Elliott Snuggs interviewed Kn Moy of Masterworks, who was doing research for the Lausanne Movement. Moy contrasted the differences between the Arab Spring and Al Qaeda. Both were powerful movements led by volunteer forces. Moy pointed out that the key difference between the short-lived Arab Spring and the sustained movement of Al Qaeda involved Al Qaeda having a small core at its center who were the keepers of the vision, mission and values. Moy suggested that Lausanne and A3 were more illustrative of movements than they were of traditional mission organizations.27

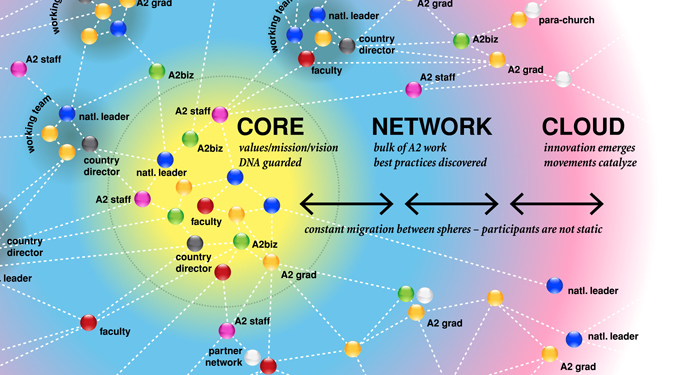

To gain insight into how CUBE Theory might operate within a networked organization, Snuggs used the model below from A3 colleague Takeshi Takazawa (see Figure 2). Given that the A3 Community is a network of pastors and NGO leaders from a number of different nations, communication practices have to adapt based on the different cultures and leadership ideals of each country. Add to this the global body of Christ interacting with each of these members of the A3 Community, and the complexities become enormous.

Figure 2a: CORE – NETWORK – CLOUD (concept from Takeshi Takazawa)28

Figure 2b: CORE – NETWORK – CLOUD close-up view

Snuggs then addresses leadership within the system:

An example might be Wikipedia. Anyone can be a part of Wikipedia as a user of the information or a creator of content. But there are values and ensuing “rules” that a core of people ruthlessly enforce. And many people who do this are not paid staff. They are a very small percentage of the Wikipedia movement who spend a huge amount of their time editing and reviewing entries. They do it because they are committed to the vision, mission and values of Wikipedia. They are a part of the core which keeps Wikipedia relevant. And they are enhanced by organizational-like units of paid staff.29

Mike Breen captures this concept from a spiritual perspective, stating, “I can assure you that if you look at the great movements of the past (whether in business, politics, societal change, etc.), what you will find in the middle is a group of people truly living as an extended family.”30 Breen’s findings on leading missional movements dovetail with Jesus’ approach of investing life into a few key disciples and encouraging them to reproduce the dynamism that he gives them in mission.

Learning from Lausanne Mission Leaders

To test these findings, I conducted and analyzed interviews with Lausanne Movement leaders to discern key issues, trends, and challenges they face, how they have grown and been formed as leaders, and how leadership has changed in the past twenty years.

I selected 20 key leaders of major initiatives and movements, collecting data through first-hand observations. Given that some of these interviews were conducted with leaders in shame-based or shame/honor cultures, Appreciative Inquiry methodology proved helpful. Appreciative Inquiry provides a positive approach to interviews, providing more fruitful and relevant material from those interviewed.

It became apparent that there were a number of common threads between the interviews. Long-standing leadership traits that several noted as constant included the spiritual aspects of missional leadership: being biblically formed, character formation, and Christ-like servant leadership. Other, more tangible threads related to the need for vision, passion, and relational competence.

Every leader pointed to a common thread in their life story—of how God clearly intervened and called them to ministry. One leader mentioned the crucial importance of a “private, personal and intimate worship of the Lord as being priority number one… [Further stating that] powerful public ministry comes from a passionate, private worship walk with the Lord.” Another leader stated, “The Church is yearning for this type of intimacy.” And another leader pointed to the importance of listening to the Lord as well as to the Lord’s speaking through others.

Globalization, economic disparity, migration, and technological advancement were all issues leaders identified as requiring changing forms of leadership. They also discussed moving away from a broad vision toward a more clearly defined set of outcomes, complete with measurable qualities, as being important in the current era.

One leader observed that “We are now living in a globalized world… We need to look at this more carefully because it impacts the Church… It impacts the whole life.” Another leader put it this way: “[We] live in an increased globalized world where issues are more than transnational. How do we fit into what others are doing and what pieces are missing and what can we do to create structures to help?”

Leaders emphasized the need for further collaboration and teamwork in diverse societies. The need for more strategic and directional leadership was also emphasized. One leader highlighted the importance of gift-based leadership rather than trait-based leadership. Another leader shared, “[Leadership is] much more dispersed and distributed (not management by objective). [We need a] vision and values approach—not [simply] by goals and objectives.”

The relational thread was strong in all of the interviews—that vision should emerge from the group more than an individual, and that people should be empowered. As one leader suggested, “giving away power” is critical to success in this age. “The ownership—confidence of indigenous leaders to lead their own way and let westerners get out of the way [will be key for leaders of the future].”

The final common thread in these interviews was a need for further creativity and innovation as we look to the future of mission. As one leader said, “[We are] constantly looking for innovative ways to engage around spiritual issues and lots of interesting methodologies in our network.” Another interviewee shared, “[We need] more emphasis on relationship, collaboration, prayer and listening to the Lord and experimentation.”

Toward a new model of global leadership

This research discovered and set the tone for the development of a more synthetic model for global leadership. Beginning with the chaotic transition of the information age to the era of globalization, the need for a change in leadership is apparent. It was discovered that leading missional movements requires different skills than those needed in past generations. We need a new understanding of leadership for the future that addresses the increased complexities.

While a catalytic person or event may provide the key launching point, a movement sustainable for the long term is led by a multiplicity of leaders. These leaders are able to cast vision and mobilize others through simple actionable steps without falling into micromanagement. Cultural and cross-cultural acumen in leading networks is paramount if a movement is to thrive in the current global context.

A team of teams, built on enduring relationships and grounded on a foundation of deep trust, makes a network or movement strong. Speed and adaptive leadership are crucial skills. The team of teams must also exhibit an ability to empower others more than themselves and foster a culture that encourages information sharing and decentralizes authority to the ground levels.

Making a difference in a complex ecosystem requires that we work together. The ability to rally people and groups around purpose and vision is critical to leading a partnership well. Building deep relational ties and developing trust bind movements and teams together. Listening to the network and movement leaders is critical, as it is in listening that the team not only feels heard, but valued.

Facilitation fosters the capacity for leaders to influence rather than directing toward an organizational objective. The importance of management skills is juxtaposed with the need to hold matters more loosely, combined with a tolerance for ambiguity, a commitment to hands-off management, and allowance for goals to be developed from a variety of cultural vantage points.

Further work needs to be done in order to contribute toward a new theory for polycentric leadership. That said, a more comprehensive model of leadership for the global era in missional movements involves all of these traits and begins to move away from more centralized forms of leadership and toward a more polycentric model.

Some traits endure through time—the importance of a solid foundation in Christ, competence, character, and a reliance on the leading of the Spirit. But it is ever more apparent that leading a movement effectively requires more facilitative and less directive approaches, ones that empower leaders at all levels throughout a movement.31

______________________________

Rev. Joseph W Handley, Jr., Ph.D. is president of A3 (formerly Asian Access). Previously, he was the founding director of Azusa Pacific University’s Office of World Mission and lead mission pastor at Rolling Hills Covenant Church. He serves on the International Orality Network leadership team.

More Information

This article was originally published in EMQ, Vol 54, Issue 2. Copyright © 2018 by Missio Nexus. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from Missio Nexus.

Used by permission from Missio Nexus, PO Box 398, Wheaton, IL 60187. Email: EMQ@MissioNexus.org. Website: www.MissioNexus.org/EMQ.

Image credits:

- Figure 1: Cube Theory from Mark Avery

- Figure 2: “Core – Network – Cloud” concept by Takeshi Takazawa; illustration by Loren Roberts, Hearken Creative Services

- Insets:

- Cycling team photo by James Thomas on Unsplash

- Lausanne logo courtesy Lausanne Movement

- Globe image courtesy of Pixabay

End Notes

1 Esler, Theodore. Movements and Missionary Agencies: A Case Study of Church Planting Missionary Teams. Fuller Dissertation, March, 2012.

2 Esler refers to the mobilization of resources toward a cause most commonly pointing to personnel and finances though other factors can be part of this as well.

3 Esler, p. 65.

4 Pierson, The Dynamics of Christian Mission. (2009: 135-149)

5 Esler, p. 52.

6 Bricolage is a word from French referring to innovation and improvisation when building something new. Oxford Dictionary of Literary Affairs, Oxford Press, p. 42.

7 Esler, pp. 93-95.

8 McChrystal, Stanley, David Silverman, Tantum Collins, Chris Fusell: Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World, Kindle location 220 Penguin Random House, New York. 2015.

9 McChrystal, loc. 1423-1424.

10 McChrystal, loc. 971.

11 Ibid, loc 1127.

12 Ibid. loc. 1581.

13 Ibid. loc. 1702.

14 Ibid. loc. 1948-1955. 15 Ibid. loc. 3576. 16 Ibid. loc 3980, 4030. 17 Butler, Well Connected. p. 41.

18 Butler, p. 51.

19 Butler, Well Connected. p. 101.

20 Ibid. p. 288.

21 Primuth, Kärin. Mission Networks: Connecting the Global Church, EMQ vol. 51, No 2., Wheaton, p. 215.

22 Avery, Mark. Beyond Interdependency: An identity based perspective on interorganizational mission. Fuller Theological Seminary dissertation 2005, p. 79.

23 Ibid, p. 96.

24 Avery Interview, January 26, 2016.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid. p.98.

27 Snuggs, Elliott. Core-Network-Cloud (Overview), Feb 21, 2015 – https://www.a2community.net/com/ih/873-core-network-cloud-overview

28 In this diagram, A2i refers to our international leadership serving the movement while A2 community refers to all of those who serve within the scope of our vision and mission. Within our movement, we have a network of leaders committed to one another and our common cause. Beyond that, each participant is engaged in activities that may relate to our mission but may not be something everyone within the movement is committed to.

29 Snuggs, Elliott. CORE – The Centripetal Force of A Movement, Part 2 (April 2015) – https://www.a2community.net/com/ih/879-core-the-centripetal-force-of-a-movement-part-2

30 Breen, Mike. Leading Kingdom Movements. Kindle loc 1079.

31 Tom Steffan, The Facilitator Era: Beyond Pioneer Church Multiplication (Wipf & Stock, 2011).